Note: varicella = chickenpox.

Chickenpox & Shingles: No Transmission is a great article on the failure to experimentally demonstrate chickenpox transmission.

In this article I will provide further evidence for the non-contagious nature of chickenpox using two publications (1, 2) unearthed by Daniel Roytas of Humanley.com, as well as some other studies I found.

Between 1912-14, Dr Frederick Thomson & Dr Clifford Price conducted human experiments in a hospital setting to assess the contagious nature of chickenpox. They conducted 54 experiments which involved putting children with chickenpox into wards with ‘healthy’ children. They were not allowed any direct contact with each other. Of the 521 ‘healthy’ children, 210 were considered ‘immune’ (40.3%) because they had contracted the disease previously, and 311 were considered non-immune (59.6%).

In just seven of the 54 experiments (12.9%) did a child become sick. Across these seven experiments, just 15 of the 521 children (2.8%) developed chickenpox. Of these, six were ‘non-immune’ (40%), one was ‘immune’ (6.6%), and the immune status of the remaining eight cases was not reported (53.3%).

Cases of disease after the encounter with chickenpox patients did occur; but it by no means follows that the contact was the cause, given that such a small percentage (2.8%) of children became ill, and no control was performed to establish the normal occurrence of chickenpox among children in the population.

In a second series of seven experiments, children with chickenpox were put into wards with healthy children. They were allowed direct contact with each other. Of the 130 healthy children, 61 were ‘immune’ (46.9%) and 69 were ‘non-immune’ (53%). None of the children (0%) developed chickenpox.

I found a paper in which this experiment was continued. Cases of chickenpox were put into wards with a total of 95 healthy children. Only 3 children developed chickenpox after more than two weeks of the introduction of the sick child; thus indicating that the contact was not the cause.

The results of these experiments are a major problem for the idea that chickenpox is a highly infectious and contagious childhood illness.

Sources:

Hess and Unger, 1918

In 1918, Alfred F. Hess and Lester J. Unger did an extensive experiment on 38 healthy children, exposing them in many different ways to the fluids of chickenpox vesicles.

0/38 became sick.

Scott, 1937

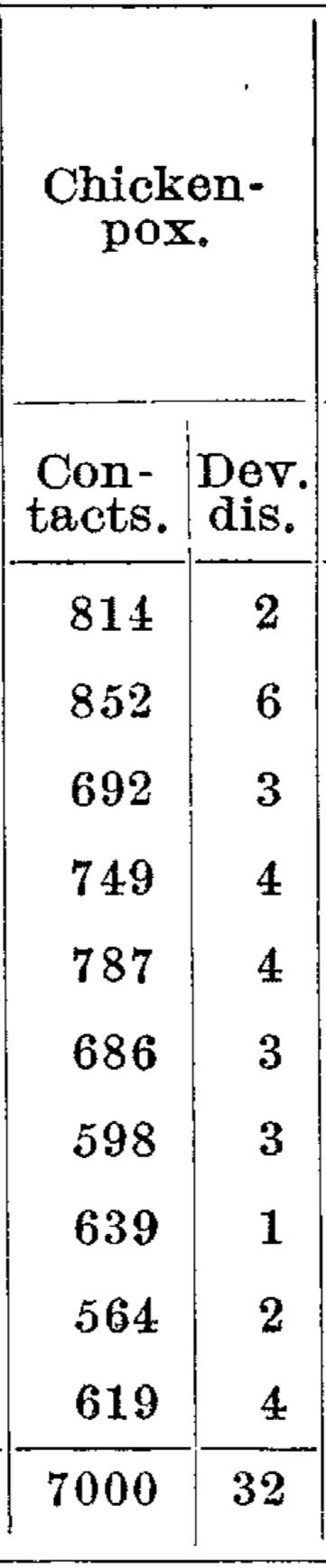

Dr. W. L. Scott, reported in a 1937 publication in The Lancet, the results of a careful investigation into the problem of “The Contact in Industry.” With regard to chickenpox he found that, over a period of ten years, out of 7000 contacts with the disease, only 32 (0.45%) subsequently developed the disease.

Greenthal, 1926

In 1926, Roy M. Greenthal inoculated 36 people with the vesicle contents of chickenpox cases.

0/36 developed chickenpox.

“The contents of a fresh vesicle is drawn into a capillary tube (after cleansing the vesicle with alcohol and saline solution and wiping dry with cotton). The contents of the tube is expressed onto the forearm of the patient to be vaccinated, and forty or fifty punctures through this fluid are made with a sterile needle; the needle merely punctures the epidermis and no blood is obtained … Thirty-six persons were vaccinated against varicella. There were nineteen “takes,” sixteen negative reactions, and one patient who left the hospital before the eighth day. No cases of varicella developed in those inoculated either successfully or unsuccessfully.”

Wats, 1937

In 1937, Dr. Wats inoculated 64 people with vesicular fluids of chickenpox cases.

0/64 developed chickenpox.

“The vesicular fluid was collected from two cases on the fourth day of the disease, suitably diluted to make a 20 per cent dilution with normal saline and filtered through a Chamberland L3 candle … An intradermal injection of 0.2 c.cm. of the appropriate solution was given on the left forearm … The controls as well as the vaccinated were observed for nine months but none contracted chicken-pox.

Tyzzer, 1906

In his 1906 publication, Ernest Tyzzer outlined a few examples of unsuccessful chickenpox transmission experiments.

“Inoculation of children with the vesicle contents of varicella has been tried in many instances, but there is great discrepancy in the results obtained. Heim, Vetter, Thomas, Czarkert, Fleischmann, Buchmüller, Smith, and others were unable to produce the disease by inoculation. Fleischmann, from his first series of inoculations, concludes that it is not possible to produce either variola or varicella by the inoculation of varicella lymph. In seven inoculations done at a later date he obtained a general eruption in one case and a local reaction in two. Buchmüller gives a series of thirty inoculations with varicella. There was some local inflammation in children so inoculated, and in one case a general varicella eruption. He regarded this as being a chance infection rather than the result of the inoculation.”

Observing skin reactions due to the injection of foreign biological material does not prove transmission, because control experiments have shown that the same results can be obtained by injecting normal “uninfected” blood.

Delpech, 1846

In 1846, M. A. Delpech inoculated two children with the fluids from a chickenpox patient.

0/2 became sick.

“M. Delpech appears to think that the Necker epidemic of varicella originated spontaneously at the hospital, but that it extended itself in the ward by contagion; for other and adjoining wards were completely free. Nevertheless, he was not able to propagate it by inoculation. Two children, in a ward where there was no eruptive disease, were inoculated with varicella fluid taken from a patient out of the hospital, but without success. This result is confirmatory of various recent experiments.”

Fleischmann 1871

A doctor named Fleischmann reported in a 1871 publication of the Medical and Surgical Journal that the inoculation of vesicle pus of chickenpox into people never induces the disease.

“Indeed, it has never been possible to produce either varicella or variola by direct inoculation of the lymph of the former on, unvaccinated subjects. Such experiments were made by Dr. Wetter (Virchow’s Archiv, 1864), and repeated by the author, in both cases without any results … Inoculation of the lymph of chickenpox on unvaccinated subjects always gives negative results.”

Did you know that arsenic poisoning can cause chicken pox and shingles? Did you know a known side effect of arsenic trioxide - chemotherapy used for leukemia - is eruptions (sometimes extremely severe) of chicken pox and shingles? Did you know a known side effect of chronic arsenic exposure can cause lesions and blisters and rashes to appear that look quite a lot like chicken pox or shingles but sometimes doctors decide it's not the virus it's just the arsenic (but other times they decide it's just the virus and not the arsenic)? The explanation for when arsenic exposure causes blisters and lesions that a doctor decides "are chicken pox or shingles" vs some other kind of blisters and lesions that "are just the poisoning" is that supposedly "the varicella zoster virus was dormant but arsenic damaged the immune system and it got reactivated."

But did you know that dogs and cats exposed to arsenic via skin contamination can develop lesions and blisters that look quite a lot like chicken pox? (It's not though, it's just poisoning!).

Did you know that the first widely used pesticide first used in the late 19th century was lead-arsenate? This was used until the 1980s. Other arsenic-based pesticides were only finally banned from use in the United States in the early 1990s (right before they started the "chicken pox vaccine" campaign).

Airborne and subsequent water contamination of arsenic has been declining in the US and UK as coal-fired power plants have been phased out, although coal ash is still a major source of arsenic poisoning that could seep into groundwater or be absorbed by plants and subsequently by wildlife or livestock feeding off contaminated grains, passing on the arsenic to other animals or humans who eat them. Rice, in particular, is highly prone to arsenic absorption.

Did you know that in England and Wales chicken pox cases were declining throughout the 80s and 90s and into the 2000s without regular chicken pox vaccination? This, of course, was as Western countries were phasing out coal-fired plants and arsenic-based pesticides.

And, of course, there are other toxic metal poisonings - acute or chronic - that can cause a variety of lesions, blisters, and rashes, that to my admittedly untrained eye, look - quite a lot like chicken pox.

I'd put links in here to various pubmed references and old medical literature but I'm too lazy.

The point is my brief foray into reviewing the medical literature seems to indicate that sometime as simple as "chronic arsenic contamination of local well water" could lead to outbreaks of "diseases that look a lot like chicken pox" or to "diseases mischaracterized as chicken pox" or "diseases that REALLY WERE chicken pox (in humans) but not chicken pox (in animals) because 'the immune system was damaged'". Take your pick.

My father used to send me to the kindergarten when there were "epidemics" like rubella and so on. I never got one.

And I was a fragile child.