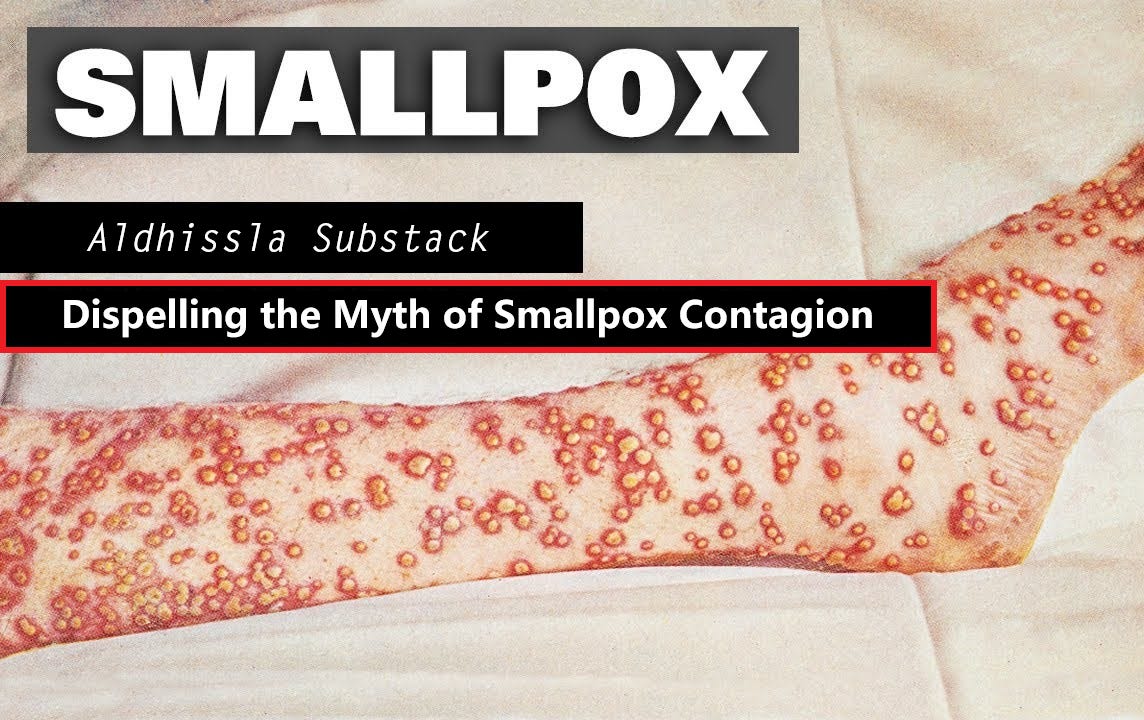

A 2004 publication entitled Smallpox: An ancient disease enters the modern era of virogenomics outlined some difficulties in the attempts to transmit smallpox to laboratory animals; stating that researchers had to restort to invasive methodologies to induce sickness in monkeys due to the failure of more natural exposure routes.

In the 1880s, Dr. Lorinser was one of the leading physicians in Vienna, Austria. He voiced his opinion concerning the idea of smallpox contagion; stating that thousands of people have been living in daily contact with people afflicted with smallpox, yet have not caught the disease. He also asserted that hospital attendants who were most exposed to contagion were not at a risk of developing smallpox (also called variola).

“But when we ask whether there is a single fact that could prove the existence of such a contagion, and its power of conveying the disease, we are bound to reply in the negative. We know, as a matter of fact, that thousands of persons, though living in daily contact with variolous [smallpox] patients, have not caught the disease; but that one single person has ever caught it by inhaling the ‘volatile contagion’ can never be proved, considering that variola, like all other diseases, can also break out spontaneously. Nevertheless, both doctors and patients cling fondly to this belief in a volatile contagion”

“… if such a thing as volatile contagion really existed, it would be found in its greatest concentration and virulence in small-pox hospitals, and nothing would be more natural than that the attending doctors and nurses should be those most frequently affected by it. Yet such is not the case. Neither in the terrible epidemic of 1871, nor in any subsequent epidemic, have I heard of a single case of a doctor or a nurse catching the disease in the Vienna smallpox hospital … And this being so, the question arises. What is it we want to disinfect? What is it we dread? In truth we do not know. That is the only answer we can give or we ought to give. The belief in infection has no scientific basis”

The non-contagiousness of smallpox is reinforced by Dr. Henry Littlejohn, who worked as a sanitary inspector. For 25 years he engaged in active sanitary work and had to deal with serious outbreaks of smallpox, and yet he never communicated the disease to his children or dependents. He did not know of any sanitary inspector who had contracted or communicated smallpox while in service.

“For twenty-five years I have been engaged in active sanitary work, and have had, with very limited staff, to cope with serious outbreaks of Cholera, Small-pox, Fever, Scarlatina, Measles, and Hooping-cough, and although I have during that period brought up a large family, I have never communicated any of these diseases to my children or dependents, nor am I aware that any of the numerous sanitary inspectors who have acted under me have ever contracted or communicated these diseases while in the public service.”

In 1849, Dr. John Evans claimed that the difficulty of tracing disease transmission provides evidence for the non-contagious nature of nearly all diseases, including smallpox. He quotes a doctor who attended 40 patients attacked with smallpox, not one of whom had been in contact with a previous case of smallpox, or consciously visited an infected neighborhood.

“But the difficulty of tracing the communication, would, if admitted as valid argument, prove the non-contagious nature of nearly all diseases. Prof. Dickson says he attended in the winter of 1847-8, forty patients attacked with small-pox, “not one of whom had ever seen a case, or consciously visited an infected neighborhood.”

In the World Health’s Organizations book entitled Smallpox and its eradication, one can read that smallpox developed in such a small proportion of people known to be in contact with smallpox patients. Careful laboratory studies showed that only 1% of household contacts to cases of smallpox developed the disease.

“However, careful laboratory studies by Sarkar et al. (1973b, 1974) showed that about 10% of household contacts of cases of smallpox harboured detectable amounts of variola virus in their oropharyngeal secretions. Only about 10% of such carriers subsequently developed smallpox.”

Of course, there is no evidence that the contact was the cause of disease; because it’s inevitable that cases coinciding with contact would occur.

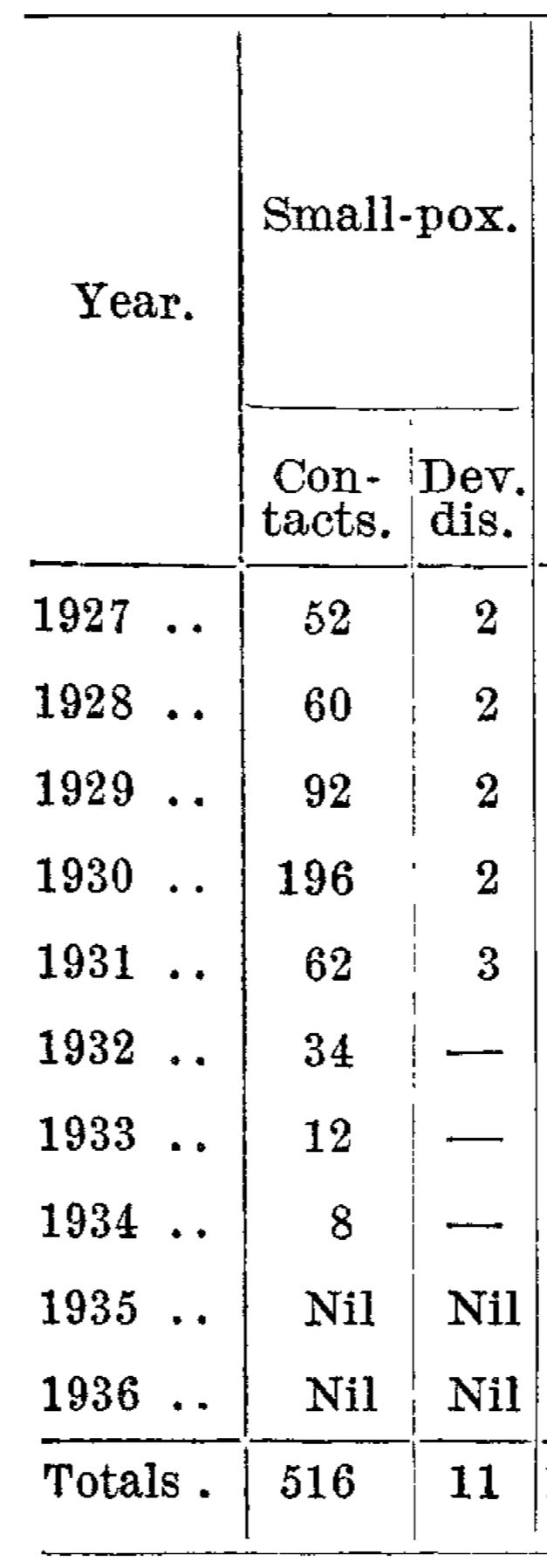

Dr. W. L. Scott, reported in a 1937 publication in The Lancet, the results of a careful investigation into the problem of “The Contact in Industry.” With regard to smallpox he found that, over a period of ten years, out of 511 contacts with the disease, only 2.1% subsequently developed the disease.

The following paragraph is an excerpt from Daniel Roytas book Can You Catch A Cold? about Dr. Rodermund’s smallpox experiment.

Dr. Matthew Joseph Rodermund, an American ophthalmologist, was a particularly outspoken critic of germ theory. He was so assured in his belief that germs were not the cause of disease, he conducted a rather questionable experiment with smallpox, that would ultimately lead to his imprisonment.

On Monday, the 21st of January 1901, Dr. Rodermund visited a young female patient with smallpox. Upon entering her room, he asked the girl’s mother if she feared contracting the disease. When the mother replied she was not afraid, Dr. Rodermund proceeded to burst open several smallpox pustules located on the girl’s face and arms to remove the fetid pus from them. He then proceeded to smear his face, hands, beard, and clothes, with the infected fluid. Rodermund was convinced smallpox was not contagious because he had performed this experiment dozens of times over the course of 15 years, each time with a negative result.

After covering himself in the pus, Rodermund returned home, ate dinner with his family, consulted with patients in his medical practice, and played cards at the local Businessmen’s Club. By his own account, Rodermund touched the faces and hands of at least 10 different people that evening. The next day, Dr Rodermund travelled by train to a nearby town, without washing his hands, face, or clothes from the night before, and mingled with those he encountered. Throughout the course of the day, he consulted with a further 27 patients, again touching their faces and hands. For almost 48 hours, Dr. Rodermund had been covered in the pus of smallpox which, according to his estimates, he rubbed onto the faces and hands of at least 37 unsuspecting individuals.

When news broke of Dr Rodermund’s actions, he was held under police guard in a quarantine facility. He somehow managed to escape this facility the evening of his arrest and travelled to a nearby town to visit an acquaintance. Shortly after meeting with his acquaintance, he was arrested for the second time in 24 hours. After four days in quarantine, he was released when the police could find nothing to charge him with. Despite directly exposing himself and dozens of people to the bodily fluids of a smallpox patient, not a single case of the disease occurred. This is odd considering smallpox is thought to be highly contagious. Dr. Rodermund’s exploits were so daring, they made headlines across the United States, and his deeds continue to be reported by media outlets to this very day.

A few years later, Dr. Rodermund performed an experiment upon 17 people in which he attempted to transmit smallpox by spraying and inhaling the diseased fluids into them. None of the people became sick.

“I made the experiments upon seventeen people between the ages of fifteen and thirty years, but in no instance could a case of consumption, scarlet fever, smallpox or diphtheria be produced.

These experiments were made in the following manner: I sprayed the poisons of diphtheria, small-pox, scarlet fever, or consumption into the throat, nose, or had them breathe them into the lungs, repeating the experiment in most cases every one or two weeks for months, with the result that no disease could be developed. Of course, I could not let the patients know what I was doing. I was supposed to be treating them for catarrh of the nose or throat.”

Dr Rodermund was hardcore 💪🏻.

Great research, thank you very much!

Thank you for your articles Aldhissla.

I appreciate how much time & effort is needed to research the information, collate it, compose it into an article, proofread & then up-load, kudos👍