The Rabies Hoax

Pasteur’s rabies deception.

Louis Pasteur’s rabies investigation began in the late 1800s. However, his initial attempts to establish the etiology of rabies were unsuccessful, as described by the Pasteur Institute.

“Louis Pasteur’s initial efforts to isolate the rabies virus proved unsuccessful as the virus remained invisible.”

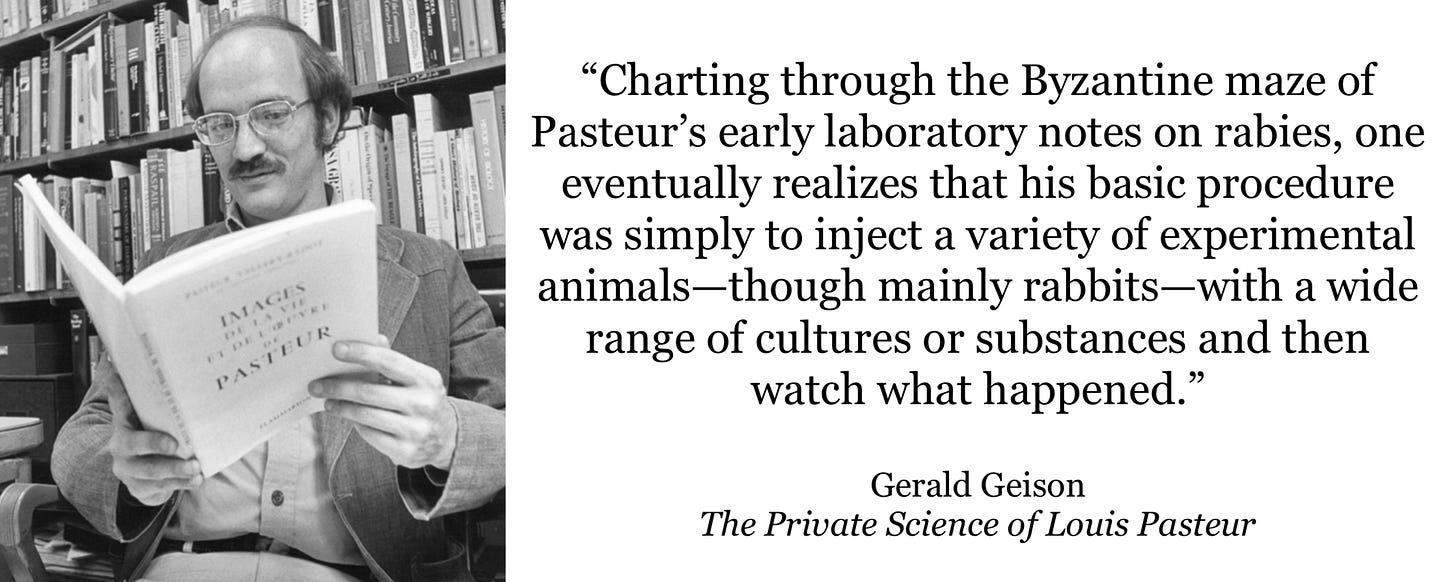

Pasteur did not give up. In his book The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, historian Gerald Geison describes how Pasteur utilized a hit-or-miss approach—inject a variety of animals with a wide range of substances and then watched what happened.

“Pasteur’s frustration becomes most evident in the notebook pages devoted specifically to efforts to find a vaccine against rabies … Charting through the Byzantine maze of Pasteur’s early laboratory notes on rabies, one eventually realizes that his basic procedure was simply to inject a variety of experimental animals—though mainly rabbits—with a wide range of cultures or substances and then watch what happened.”

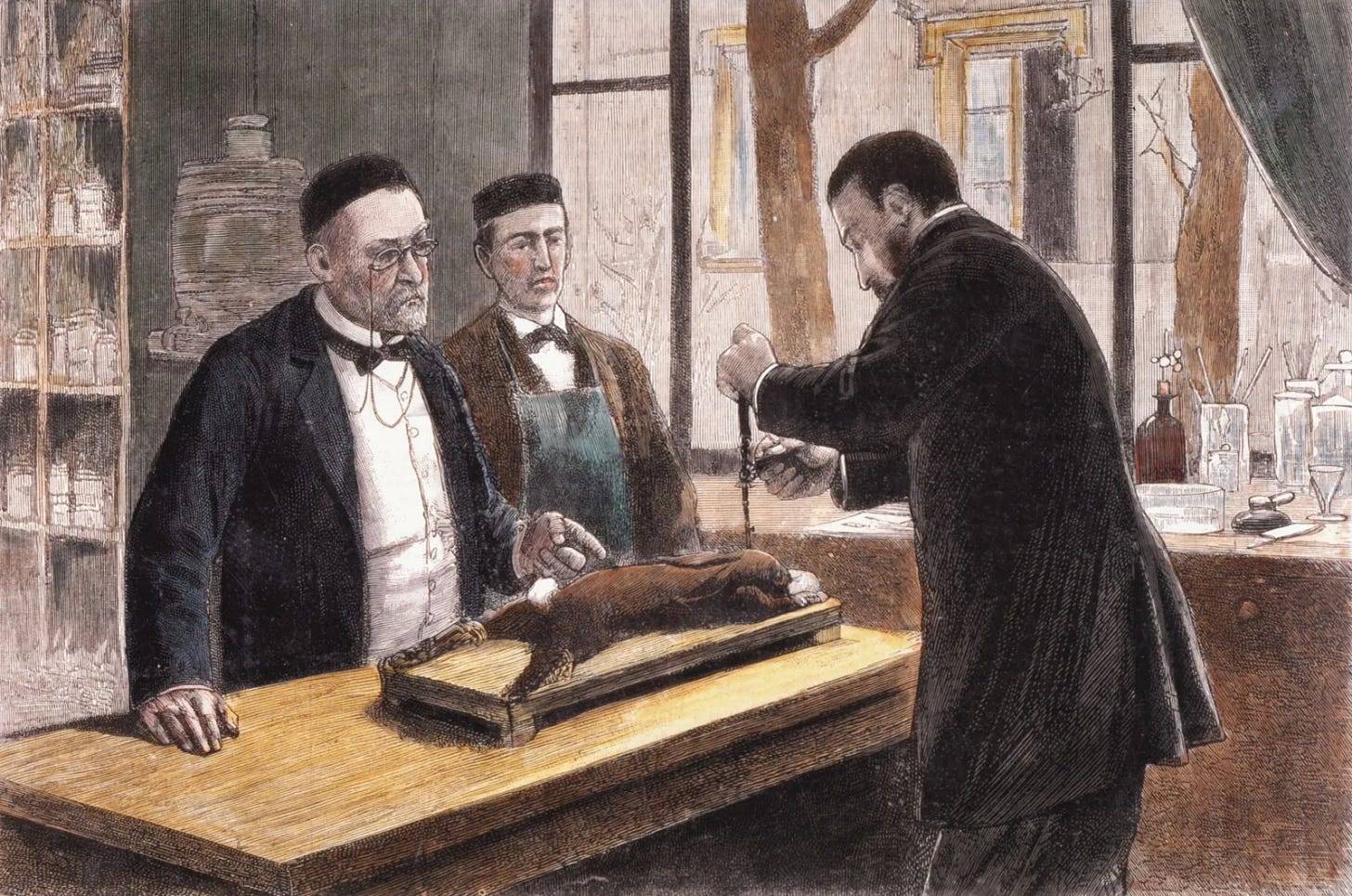

Eventually, he discovered a successful method. Pasteur would use the nervous tissue from a diseased animal and inject it directly into the brain of a healthy animal through a hole drilled into its skull.

“But as rabies is a disease of the nervous system, together with Emile Roux, Louis Pasteur then had the idea of inoculating part of a rabid dog’s brain directly into another dog’s brain. The inoculated dog subsequently died.

The experiment was then conducted on rabbits as the risk for the experimentalists was less than with rabid dogs.”

This highly invasive methodology did not reflect how an animal would presumably acquire the disease in the natural world.

According to Dr. G. Archie Stockwell in 1886, it was not surprising that the animals became diseased, because such an inoculation is invariably attended with consequences to the creature operated on, with paralysis as a frequent complication—no hypothetical pathogen required.

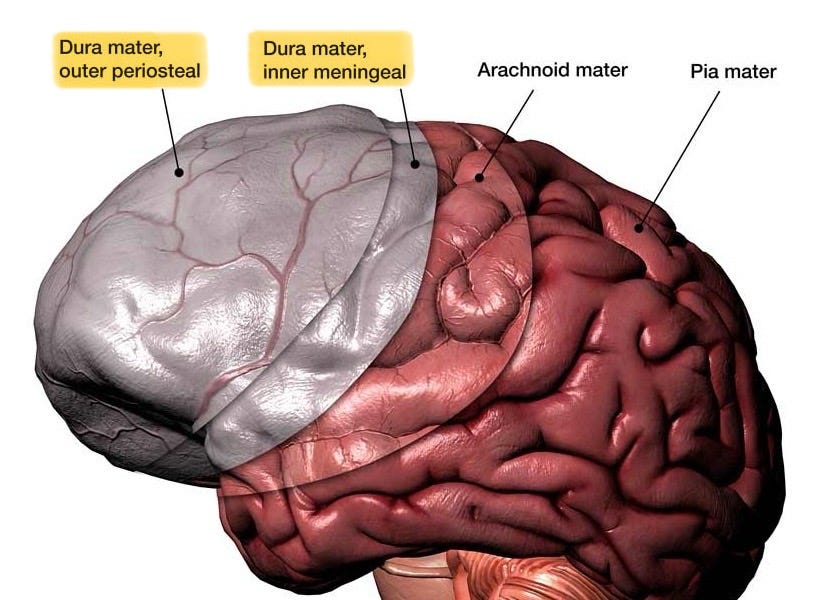

“Every physiologist or pathologist knows that intradural inoculation,—the means employed by Pasteur to secure “infected” (?) spinal cords,—even of the simplest septic or aseptic product, is almost invariably attended with consequences most grave to the creature so operated upon. Naturally, paralysis most frequently follows, yet it is the evidences of paralysis upon which Pasteur so confidently relies for his diagnosis of rabies. If an opening be made in the cranium of the dog, or the rabbit, directly over the nerve-centres,—and the nervous system of either is much more impressible than that of man, and a drop of pus, blood, or bouillon introduced in the submeningeal space, the miracle would be if the creature did not speedily develop a paralysis of facial muscles and posterior extremities!”

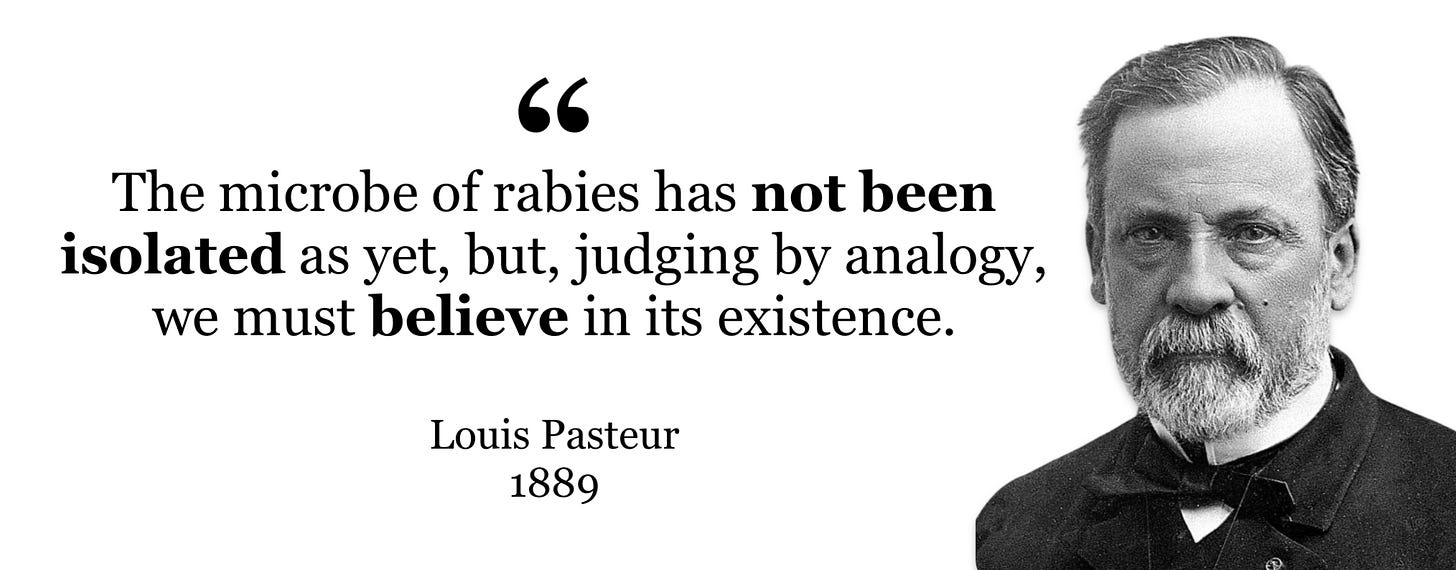

Louis Pasteur was never able to purify and isolate a rabies microbe. Despite his failure to identify the causative agent he expected to find, he never wavered in his belief. His invisible white whale remained just that—a belief.

“The microbe of rabies has not been isolated as yet, but, judging by analogy, we must believe in its existence.

Pasteur clung to his belief in an invisible enemy, adjusting his approach to fit his narrative rather than letting evidence guide him. He mastered the art of manipulating fear and fantasy, convincing people to line up for his toxic treatments.

Pasteur’s neglect of controls in his animal experiments was noted by Dr. Thomas M. Dolan in his 1886 article entitled M. Pasteur’s Prophylactic.

“Control experiments were neglected.”

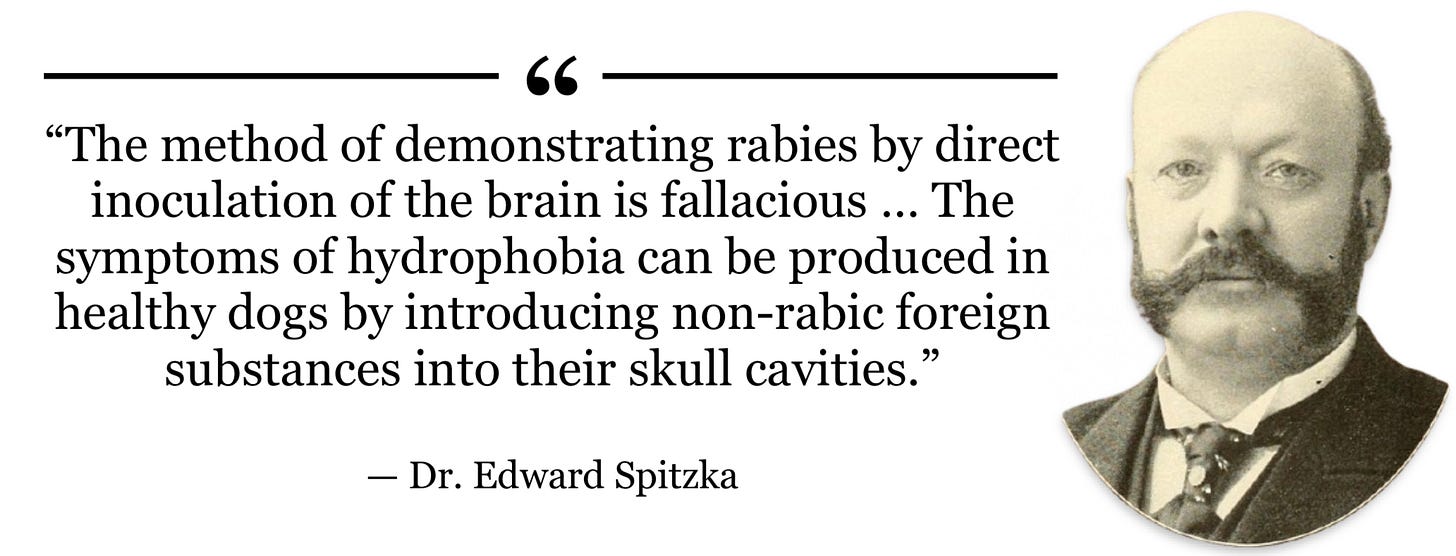

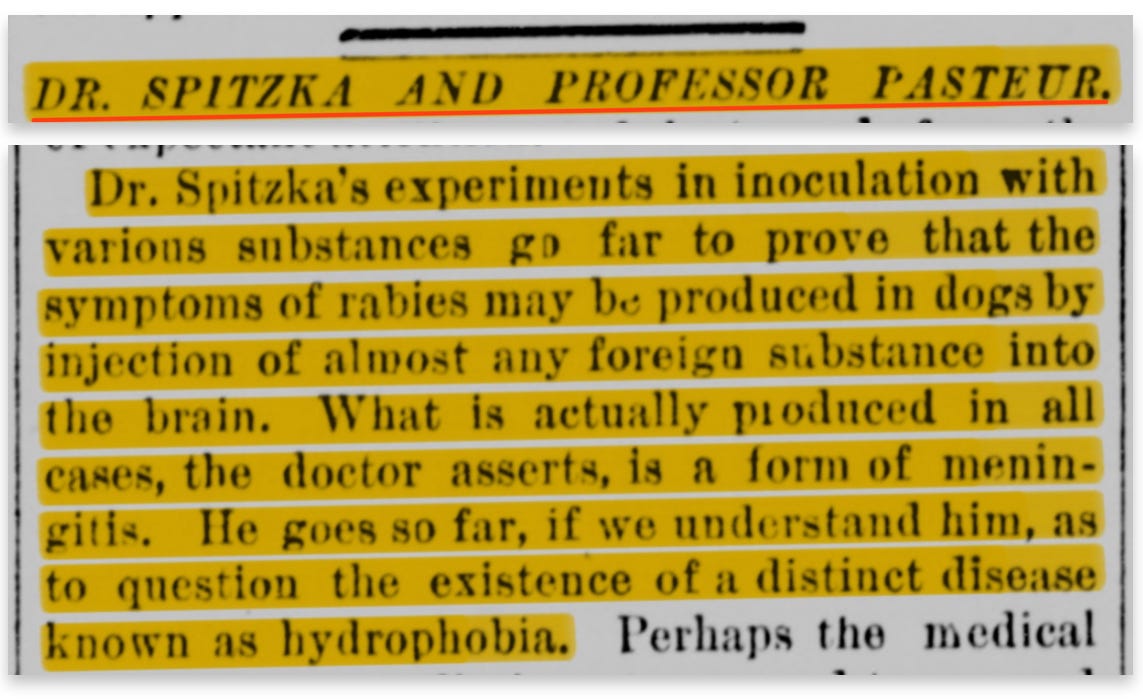

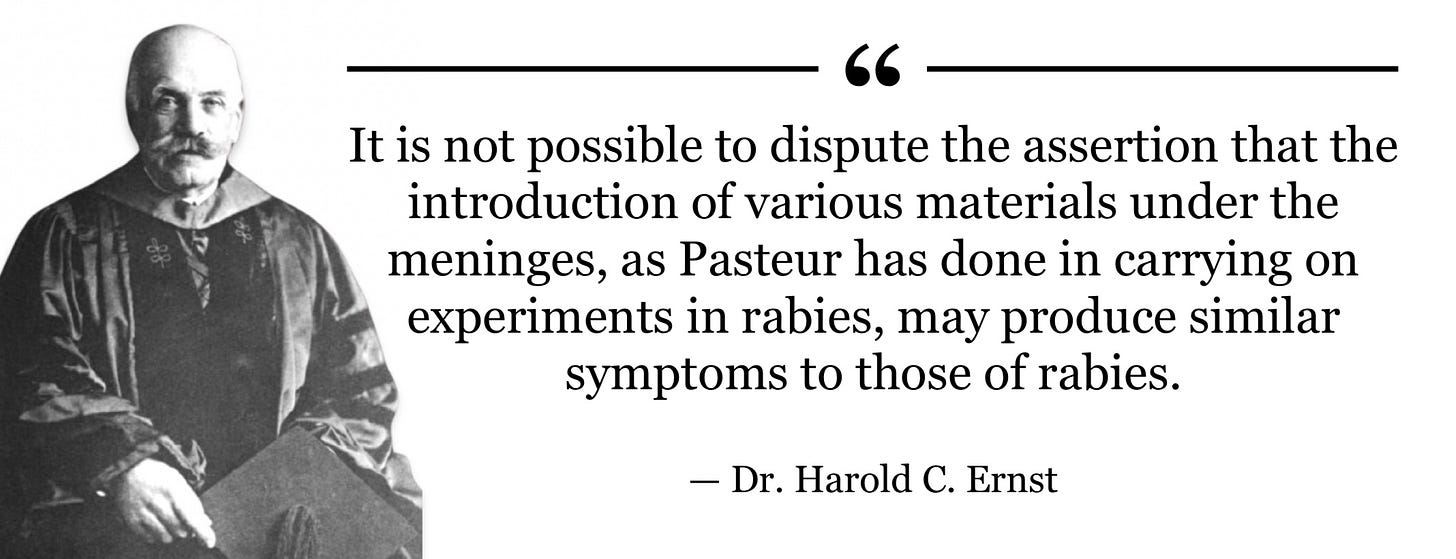

Dr. Edward Charles Spitzka was an eminent late-19th century psychiatrist, neurologist, and anatomist.

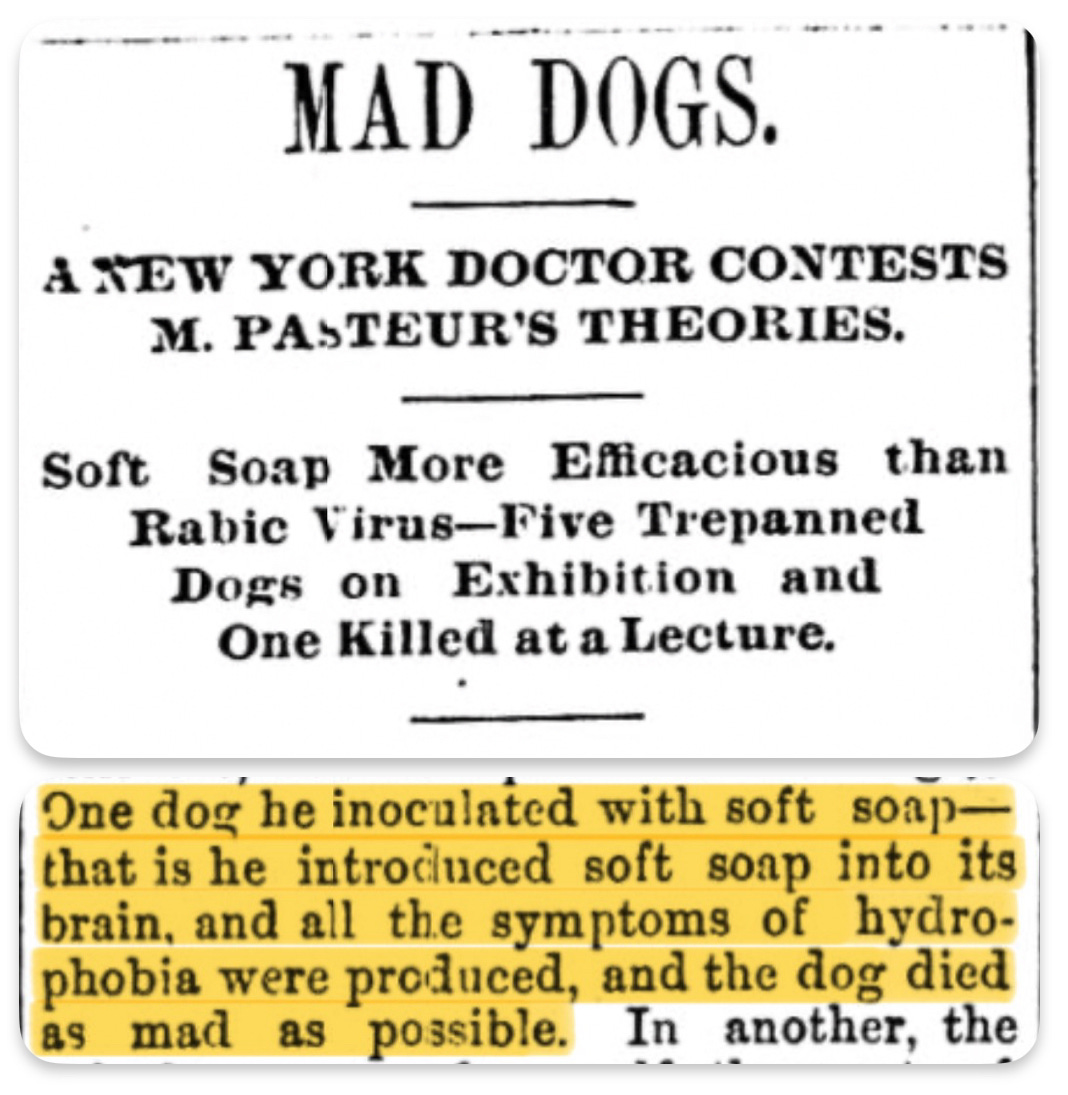

Dr. Spitzka was particularly critical of Louis Pasteur. In order to disprove Pasteur, Spitzka conducted experiments to show that foreign substances injected into the brain would cause inflammatory disturbances, the symptoms of which would be identical to those of “rabies.” He injected into the brains of dogs varied substances such as calf tissue and even soap.

“The experiments that Dr. Edward C. Spitzka has been conducting at the Veterinary Infirmary in East Fourteenth street, in support of his theory that rabies or hydrophobia can be produced in dogs by the insertion into their brains of any foreign substance, have satisfied him, so he says, of its truth.

Of six healthy dogs inoculated, five have died. Some portions of the spinal cord of a healthy calf and other substances were introduced into their brains.”

By establishing that symptoms of nervous system disturbance and paralysis could be produced by introducing non-rabic foreign substances into the brain of dogs, Spitzka demontrated that Pasteur’s rabies method was invalid. He published his results in The Journal of Comparative Medicine and Surgery (an alternative link can be found here).

“I am not aware that any one has yet isolated the microbe of hydrophobia. What purports to be such is also found in the healthy dog. There is besides no symptom of hydrophobia that may not be produced in dogs inoculated with decayed fluids, the spinal cord of a calf, or with soap, or with olive oil injected into the circulation.”

As previously stated, Pasteur preferred to inoculate rabbits, due to the convenience.

However, Dr. N. E. Brill reported in his 1887 publication that the symptoms of “rabies” in the rabbit were vague and indefinite.

“The symptoms of hydrophobia in the rabbit are vague and indefinite. No two authors and experimenters have found them to be the same.”

Together with Dr. Edward Spitzka, he was able to produce paralysis in rabbits by the inoculation with spinal cords from healthy animals.

“We have been able to produce paralysis in a rabbit by inoculation with healthy spinal cord which had been treated in the manner described by Pasteur.”

They utilized the spinal cords of these paralytic rabbits and inoculated them into dogs, and produced in the dogs the symptoms which have been ascribed to as rabies.

“In a series of experiments made a little over a year ago, in connection with Dr. E. C. Spitzka, we found that we could produce the symptom-complex assigned to hydrophobia in rabbits by inoculating with septic material, or with the healthy spinal material of another rabbit; but the symptoms varied, with the exception of paralysis, which was constant in each, almost as often as the number of experiments … We utilized the spinal cords of these paralytic rabbits prepared in strict accordance with Pasteur’s directions and inoculated them into dogs, and produced in the dogs those symptoms which have been ascribed to dumb rabies in the dog.”

Dr. G. Archie Stockwell reported in an 1888 issue of the Therapeutic Gazette, that he was able to induce the symptoms alleged to mark rabies in rabbits by the inoculation of saliva from various healthy creatures.

“The writer, during a series of experiments, developed all the symptoms alleged to mark hydrophobia, or rabies, in rabbits by the intradural inoculation of healthy saliva taken from various creatures, man included; also by tartar from human and canine teeth!”

Thus, the symptom complex Pasteur observed in rabbits following the intracerebral injections was simply a result of the experimental procedure itelf.

“M. Pasteur produced a disease in rabbits which he called rabies. The same kind of affection in rabbits can be produced by injecting almost any kind of diseased material into the same region favoured by M. Pasteur.”

In a study entitled The Effects of the Injection of Normal Brain Emulsion into Rabbits published in 1932, Dr. Edward Hurst established that the injection of normal brain emulsions into rabbits leads to severe toxic manifestations, including paralysis and death.

“The introduction parenterally in rabbits of emulsions of normal brain tissue is followed by severe toxic manifestations leading to wasting and death. In a few cases paralyses occur.”

The results of these control experiments made physicians doubt the validity of Pasteur’s inoculation practice. In a paper published in The Lancet by surgeon-general Charles A. Gordon, the diagnostic method of intercranial inoculation was brought into question—due to the fact that animals likewise took sick when innocuous matter from healthy animals were injected in the same manner.

“The reliability as a crucial test of intercranial inoculation as practised in Paris is by no means generally accepted; on the contrary, effects identical in character have followed similar inoculation from healthy dogs with innocuous matters and from the preliminary operation in the absence of any inoculation.”

In fact, the existence of rabies as a disease was questioned by many, Dr. Gordon describes.

“Opinions differ as to the existence of rabies as a definite and specific disease due to one particular cause, and to it only, or as an attendant condition in the course of various maladies.”

As early as 1826, a surgeon named Robert White doubted that rabies (hydrophobia) was a specific disease spread by the bite of a dog. In his book entitled Doubts of Hydrophobia as a Specific Disease to Be Communicated by the Bite of a Dog, he describes how he inoculated himself with the fluids of a presumably rabid animal without becoming sick.

“I have also inserted a portion of the supposed poison on the point of a lancet in my own arm, an experiment I would at any time repeat, but without any effect, not even the slightest irritation succeeding the wound.”

According to Dr. Charles Gordon, the symptom complex termed ‘rabies’ or ‘hydrophobia’ was looked upon by many physicians as a non-specific condition resulting from various causes.

“By a considerable number of capable observers hydrophobia is looked upon as not being itself a specific disease due to one cause alone, but as a “condition” resulting in different cases from various causes, including traumatic injuries and nervous “shocks,” as a complication in the course of various diseases, and as occurring in the absence of apparent cause. In these respects the disorder is referred to the class of maladies which includes also tetanus, epilepsy, chorea, &c.”

In agreement, Dr. G. Archie Stockell concluded that the disorder termed hydrophobia, or rabies, is merely a development of irritated nerves arising from numerous and variable causes.

“The conclusion is rapidly being forced upon thinking and observant minds that so-called hydrophobia is merely a development of irritated nerves arising from numerous and variable causes, wholly devoid of elements of specificity.”

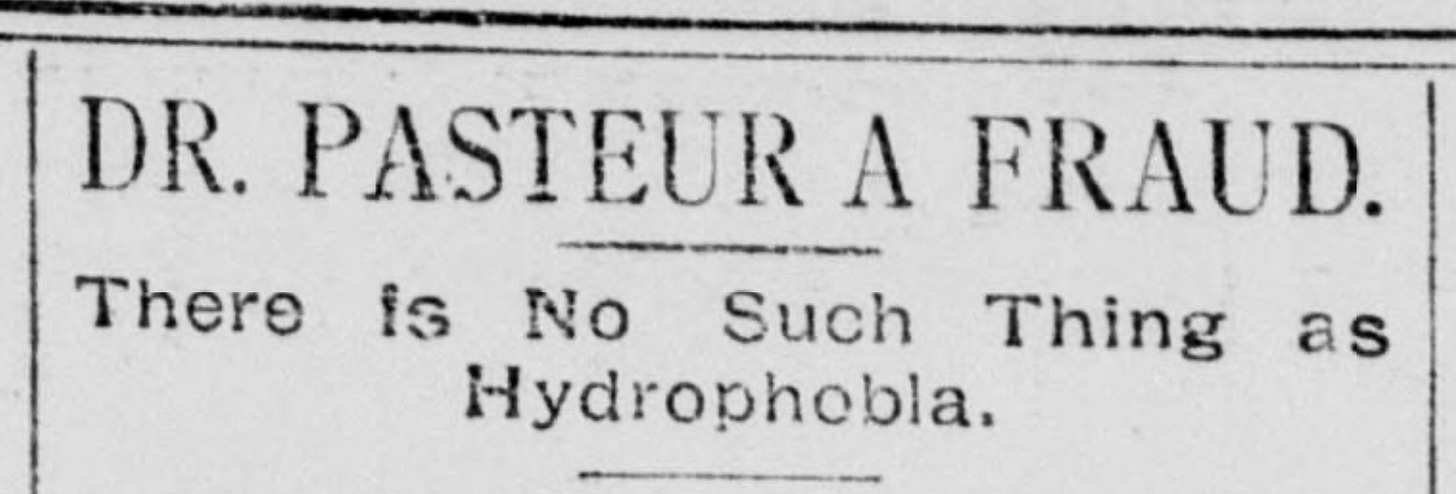

In an article entitled Dr. Pasteur a Fraud - There Is No Such Thing as Hydrophobia, Dr. J. M. Crawford states that rabies is an old established superstition.

“I do not believe that there is such a disease. And furthermore, I don’t think you will find many reputable physicians who do believe in it. This feeling has been a growth of recent years, and has come with the improvement in the art of diagnosis. It is an old established superstition, a tradition, that the saliva of a mad dog is a deadly poison, and people won’t get it out of their heads for a long time yet. But physicians shake their heads now and look dubious at the mention of hydrophobia.”

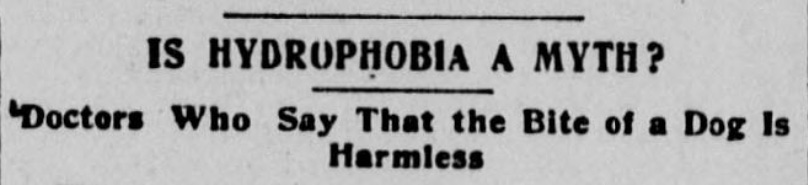

Dr. Joseph W. Hearn, professor of clinical surgery, claims that the bite of a dog is no more dangerous than the scratch of a pin, in a 1896 article entitled Is Hydrophobia a Myth?

“It is encouraging to be informed by distinguished professors of medicine and surgery that hydrophobia is, at best, a theory and has no actual existence. It belongs, according to a pamphlet recently published in Philadelphia, to the class of simulated diseases. “I am of the opinion,” says Dr. Joseph W. Hearn, professor of clinical surgery in Jefferson Medical college, “that the bite of a dog is no more dangerous than the scratch of a pin”

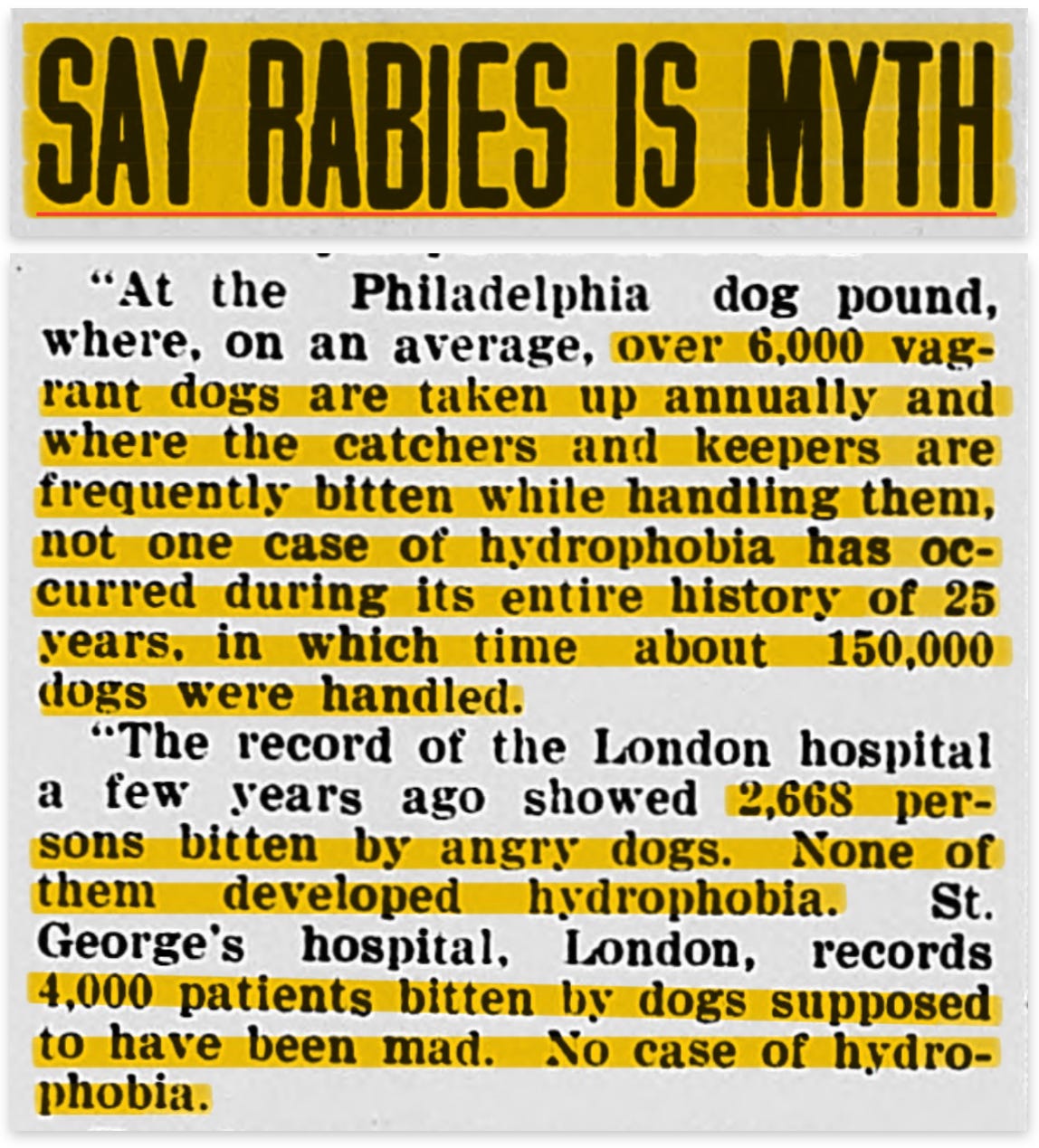

Dr. Matthew Woods published an article in 1896 in which he provided evidence of the non-existence of rabies. In Philadelphia, 150,000 vagrant dogs were handled without a single case of rabies. In London, of the 2,668 patients that had been bitten by angry dogs, not one had developed rabies, and in another hospital in London, no case of rabies developed in 4,000 patients bitten by supposed rabid dogs. After sixteen years of investigation, Dr. Charles W. Dulles failed to find a single case on record that could be conclusively proved to have resulted from the bite of a dog.

“At the Philadelphia Dog Pound, where, on an average, over six. thousand vagrant dogs are taken up annually, and where the catchers and keepers are frequently bitten while handling them, not one case of hydrophobia has occurred during its entire history of twenty-five years, in which time about 150,000 dogs were handled.

The record of the London Hospital a few years ago showed 2,668 persons bitten by angry dogs. None of them developed hydrophobia. St. George’s Hospital, London, records 4,000 patients bitten by dogs supposed to have been mad. No case of hydrophobia.

Finally, Dr. Charles W. Dulles, lecturer on the History of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, who has had the honor of being repeatedly appointed by the medical societies of the State to investigate rabies, and has read various papers on the subject before the American Medical Association, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia County Medical Society, the Medical Society of Pennsylvania, the Medico-Legal Society of New York, and has corresponded on the subject with most of the distinguished medical men of Europe, a physician familiar both with the literature of rabies, the history of Pasteur and the institutions called by his name, and who in addition has performed the almost incredible task of investigating, either personally or by correspondence with the physician or others in attendance, every case reported in the newspapers of the United States for the past sixteen years, shows that hydrophobia is extremely rare, so much so that he inclines to the view that “there is no such specific malady,” having “after sixteen years of investigation failed to find a single case on record that can be conclusively proved to have resulted from the bite of a dog”

A 1897 newspaper reported that over 100.000 dogs were handled by agents without protection, many of the dogs were supposedly rabid — yet no one ever got rabies, despite frequent bites and scratches.

“Dogs are shot or clubbed to death daily for rabies when they are simply ill, just as a man might be, and not mad. A dog may tumble down in a fit, but he isn’t mad. He may have trouble with his stomach and sulk, but he isn’t mad. He may have epilepsy and froth at the mouth, and not be mad. Within the last four years our agents have handled over 100,000 dogs and over 150,000 cats. They have been called upon to shoot so-called mad dogs, and instead of doing so have picked them up in their arms and put them into the ambulance. They have been scratched and bitten again and again at our shelters. Sometimes they have had an arm or a hand crushed by a savage bite, and have had to stay a week in hospital; but no one of them ever had hydrophobia”

“Some of the most celebrated physicians in the world do not hesitate to say that there is no such thing as hydrophobia … Some eminent physicians look upon the disease as purely imaginary, as witchcraft.”

The Daily Pioneer wrote in 1903 about a dog warden that had been bitten or scratched over 300 times. Many of the dogs were mad and frothed at the mouth — yet he didn’t develop rabies.

“Scientists and veterinarians of this day are pretty generally agreed that hydrophobia is largely superstition; that the people of this country are needlessly worrying themselves about “mad” dogs, very much to the benefit of “institutes” that “cure” dog bites.

During the past twenty years the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals of Hudson, N. J., has employed about twenty different dog wardens, who are constantly handling dogs of all degrees and of all ailments, but hydrophobia is unknown to any of these experts.

One of these wardens, employed continuously for the last seven years by that society and the Jersey City board of health, has handled in that time nearly 10,000 dogs, always catching even the most vicious with bare hands and without the aid of gloves, nets or accessories.

He was bitten or scrached over 300 times, and bears eighty marks from these mutilations—bitten by alleged mad dogs many times, in some instances where they frothed at the mouth.”

A number of other diseases besides “rabies” have the common features of dread and inability to swallow water, as maintained by Dr. Irving C. Rosse.

“The chief reason then for skepticism in regard to this badly elucidated disease seems to be the faulty nature of the evidence. Many of the so-called cases, when thoroughly sifted, resolve themselves into some distinct, recognizable disease, generally hysterical or nervous, in which terror and expectant attention are the main factors. In fact a number of other diseases besides hydrophobia have the common features of dread and inability to swallow water, associated with convulsive movements and psychic manifestations.”

The hallmark symptom of rabies is considered to be dysphagia (hydrophobia). However, as stated by Dr. Matthew Woods, this condition is non-specific and can be featured in atleast 30 other diseases besides rabies.

“We are aware that dread and inability to swallow water, associated with convulsive movements, and striking manifestations are common features of at least 30 other diseases besides rabies.”

Such was outlined in Dr. Charles Dulles publication entitled Disorders Mistaken for Hydrophobia, in which he noted that the symptoms of hydrophobia appeared in no fewer than thirty disorders—and likely many more.

“Meningitis, whether cerebral or spinal, may give rise to all the symptoms of excitement and dread of drinking which are commonly attributed to hydrophobia.”

In a case report of polio for example, the non-specific symptoms of rabies were present.

“On attempting to drink some of the fluid, swallowing was evidently difficult and accompanied by much pain. There was considerable mucous flowing from the nose and mouth, the mucous being thick and ropy.”

In the dog, the symptoms ascribed to as rabies may be induced by various causes, as outlined by Dr. Stockwell.

“Excessive saliva in the canine is induced by all forms of fatigue, by affections of the ear and throat, mouth and teeth,—especially dental caries,—eating of “dog” or “quitch” grass (Triticum repens), distemper, choking, inflamed wounds, fear, paralysis, etc.; and paralysis, independent of rabic condition, is a concomitant of many local, sympathetic, brain, and nerve disorders. The same is also true of twitching of eyes, eyelids, jaws, muscles, etc.; of lolling tongue, indrawn tail, updrawn flanks, drooping head, slinking gait, and wandering habit (the last is much more likely to be due to a taste for mutton than any disease); one and all, save as indications of misery and suffering, are not of the least value alone, and nearly all are present in mastoiditis, anæmias, fevers, and the lesser forms of illness.”

Rabies has also been shown to arise idiopathically (spontaneously), according to Dr. Charles Gordon.

“That the condition so described has in particular instances arisen idiopathically is attested by observers whose statements are beyond question.”

In 1931 for example, Dr. E. Weston Hurst documented an outbreak of rabies without a history of bites.

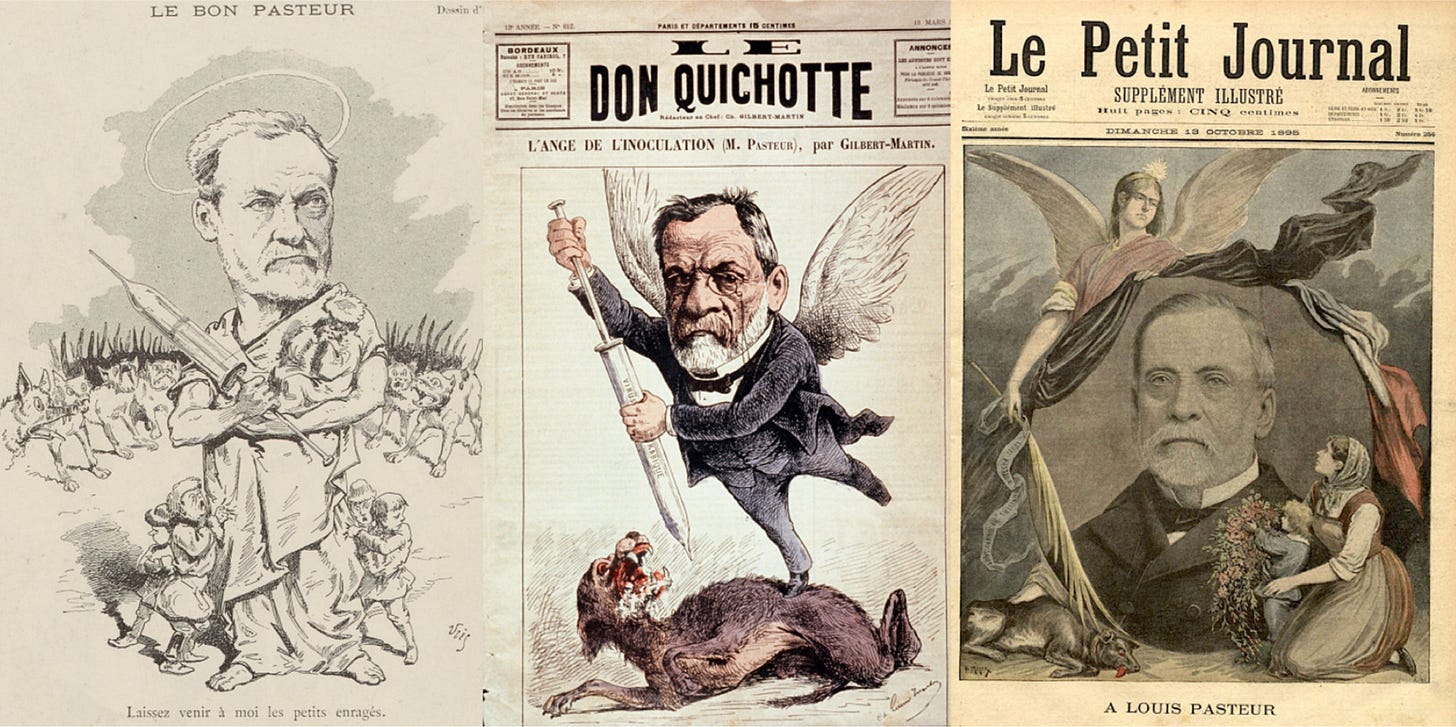

Louis Pasteur gained fame and recognition, despite the problematic nature of his rabies research. But this was largely a consequence of the popular press, wrote Dr. Elmer Lee, Vice President of the American Academy of Medicine.

“So great is the influence of the modern press that a scientific proposition, while still in the germinative state, is heralded throughout the civilized world, and is quickly transformed into a perfected science by writers of the press. There were a few who were able to doubt the truth of the allegation as to the curative influence of the Pasteur lymph. Long before cool and scientific inquiry could be made by physicians away from this center of discovery, the die had been cast that hydrophobia was curable by Pasteur lymph. At this present moment there are unmistakable proofs that error in judgment and in practice is the largest element in the hydrophobia cure.”

Pasteur became alarmed at his own work due to the many deaths among the patients, according to Dr. Lee.

“During the first few years of the experimental inoculations for rabies, many deaths occurred among the patients; so many, in fact, that Pasteur himself became alarmed at his own work.”

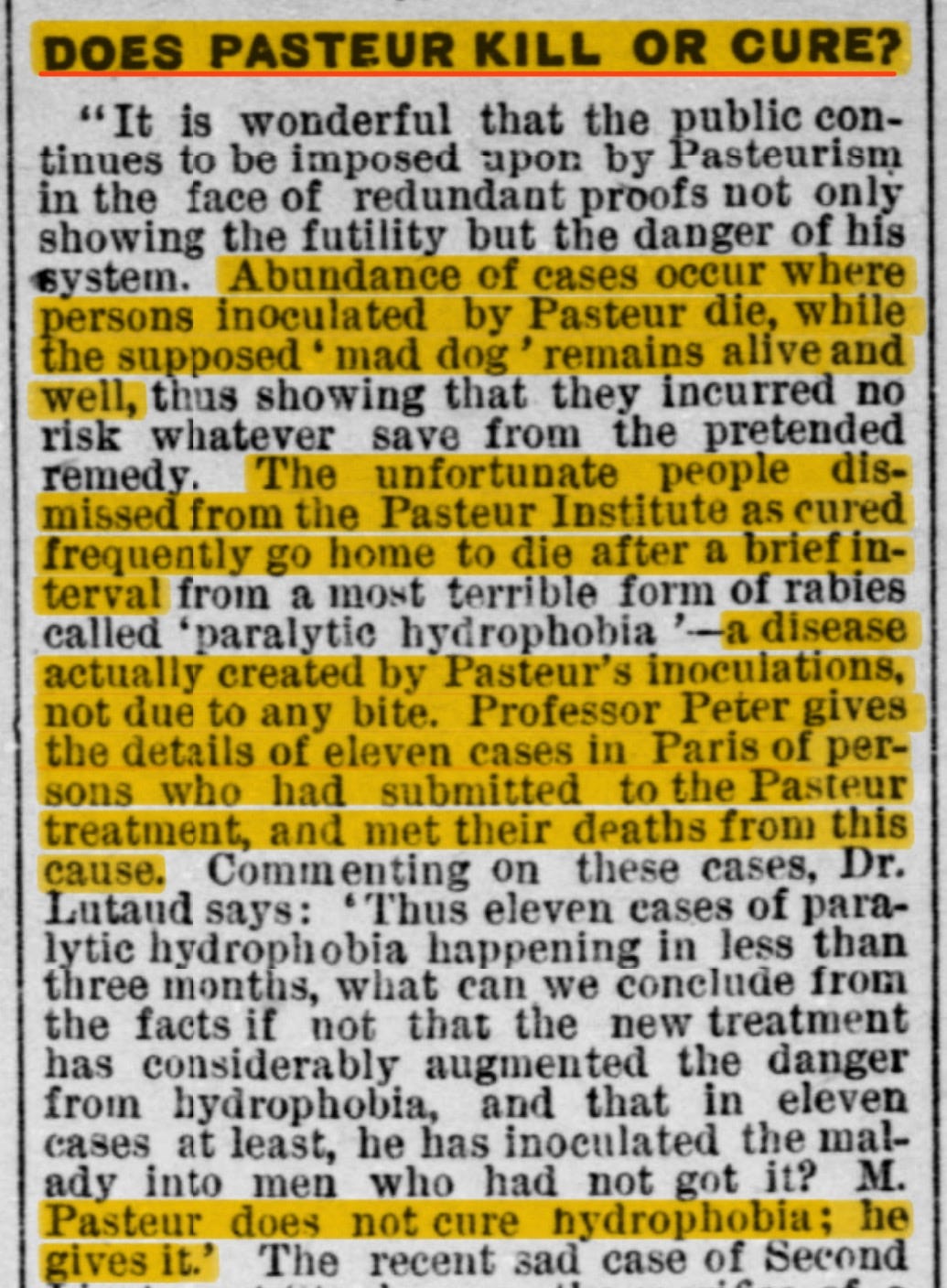

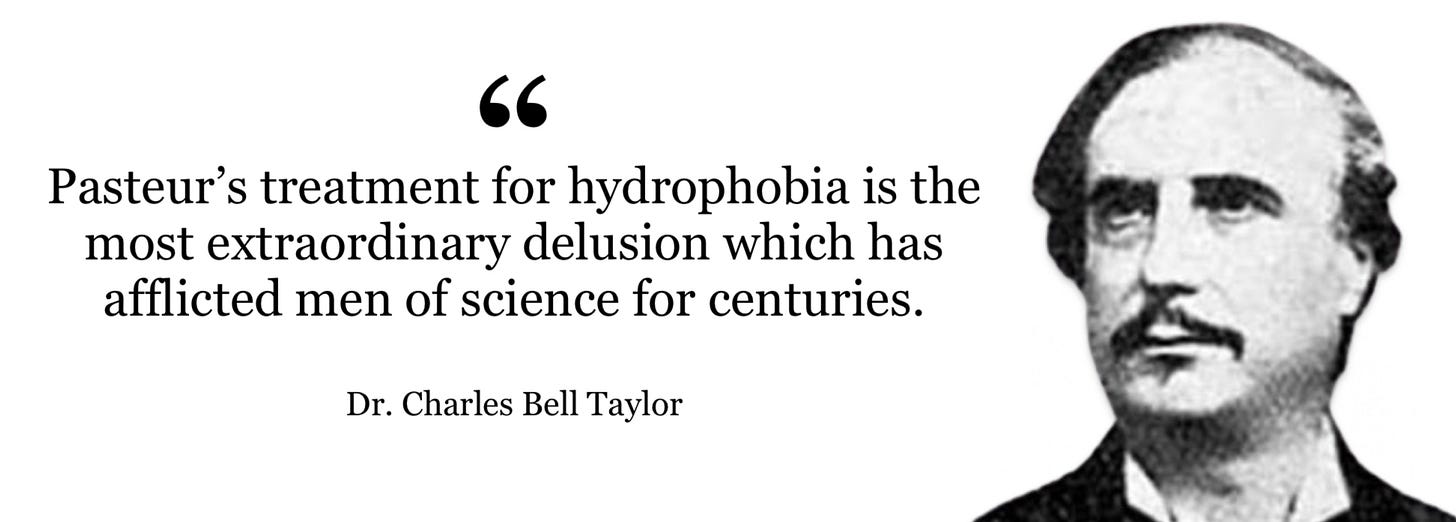

Dr. Charles Bell Taylor of England strongly condemned Pasteur’s treatment for rabies.

“Pasteur’s treatment for hydrophobia is the most extraordinary delusion which has afflicted men of science for centuries.”

“I am entirely in agreement with you that M. Pasteur’s so-called preservative against hydrophobia is at once a mistake and a danger.”

— Professor Michel Peter, member of the Academy of Medicine, Paris

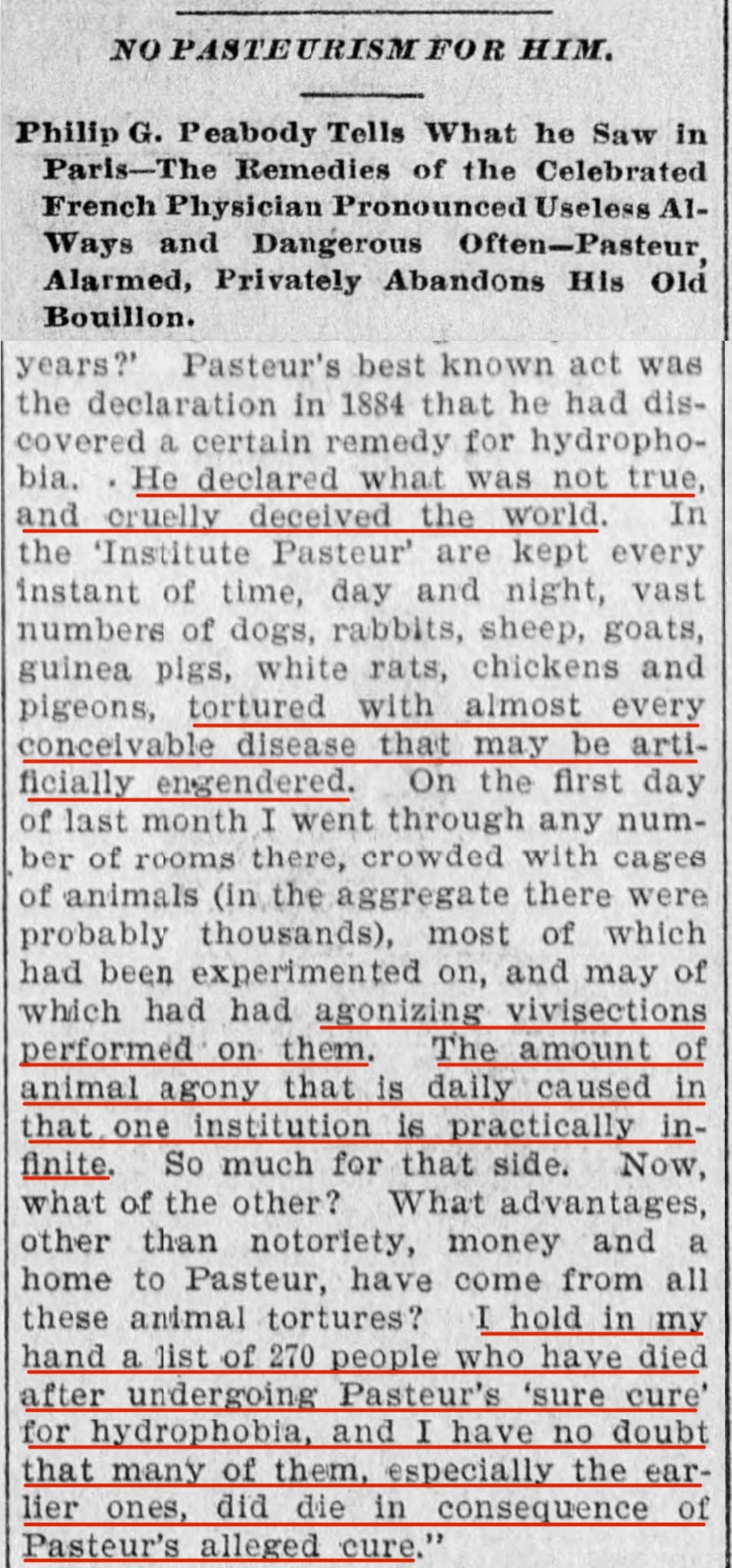

Pasteur was accused of cruelly decieving the world in a 1895 article entitled The Remedies of the Celebrated French Physician Pronounced Useless Always and Dangerous Often.

“Pasteur’s best known act was the declaration in 1884 that he had discovered a certain remedy for hydrophobia. He declared what was not true, and cruelly deceived the world … I hold in my hand a list of 270 people who have died after undergoing Pasteur’s ‘sure cure’ for hydrophobia.”

Pasteur’s Anthrax Disaster

In the early 1880s, Louis Pasteur released a vaccine for anthrax, a disease which primarily afflicts livestock.

Robert Koch's Tuberculin Disaster

In 1890, Robert Koch presented a paper entitled On Bacteriological Research to the International Medical Congress, in which he declared that he had developed a substance that hindered the growth of tubercle bacilli.

The Tuberculosis Hoax

The disease now called tuberculosis was formerly known as consumption, phthisis, the white plague, and scrofula. Keep this in mind when reading through the historical texts in this article.

Well done, the drilling holes in heads always seems so absurdly ridiculous that it's hard to comprehend how anyone accepted that as evidence of anything other than insanity.

Your article is top notch, thanks.