In 1890, Robert Koch presented a paper entitled On Bacteriological Research to the International Medical Congress, in which he declared that he had developed a substance that hindered the growth of tubercle bacilli.

The announcement was hailed with great enthusiasm, and tuberculosis patients began to converge on Berlin.

“Europe witnessed a strange but not unprecedented spectacle last month. In the Middle Ages the discovery of a new wonder-working shrine, or the establishment of the repute of the grave of a saint as a fount of miracles, often led to the same rush which has taken place last month to Berlin ... The consumptive patients of the Continent have been stampeding for dear life to the capital of Germany. The dying have hurried thither, sometimes to expire in the railway train, but buoyed up for a time by a new potent hope.”

An editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association mocked the response to the news of Koch’s new “cure.”

“Think of it! Thousands of physicians—Germans, Austrians, Italians, Russians, English and Americans (and possibly those of other nations), flocking to Berlin to see Prof. Koch’s treatment, scrambling for places, and offering fabulous prices for a few drops of the liquid whose composition they do not know and cannot find out! And when asked why they want it, reply, “Because Koch thinks it will cure tuberculosis!” When has the practice of medicine witnessed such a spectacle?”

According to Koch, tuberculin was ineffective when administered orally and had to be injected subcutaneously.

In his 1890 presentation, Robert Koch describes how bacteriologists had only produced such insignificant practical results, in spite intense efforts.

“Up till now I have purposely left one question untouched, although it is precisely the one which is most frequently, and not without a certain amount of reproach, addressed to bacteriologists. I mean the question of what profit all the weary labour which has up to the present been expended on the investigation of bacteria has been? … We have hardly any directly acting, that is, therapeutical, agents to place beside the indirect ones … Although in these directions, in spite of endless toil, bacteriological research has only such insignificant results to show.”

With Koch’s sensational announcement of a cure for tuberculosis, bacteriology and germ theory was on trial, as stated by an article in The Lancet.

“Indeed, apart from the fact that we may be on the verge of a revolution in therapeutics, it may be said that bacteriology itself is on its trial in this momentous investigation.”

Koch had based his conception of a cure on a previously acquired understanding that germs were the cause of tuberculosis.

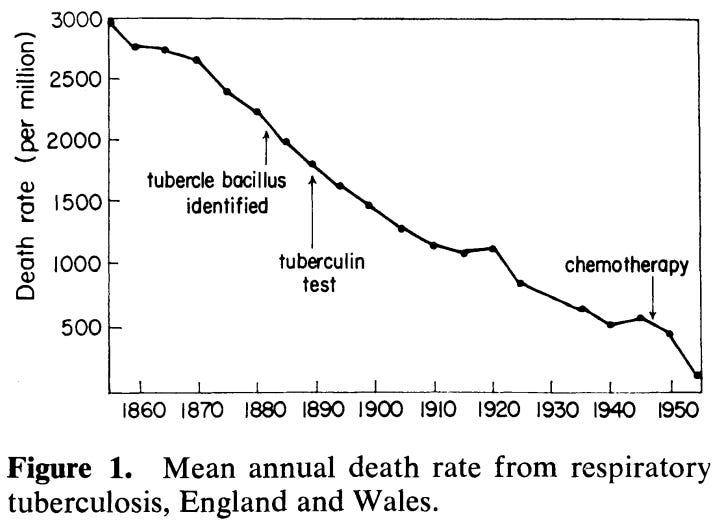

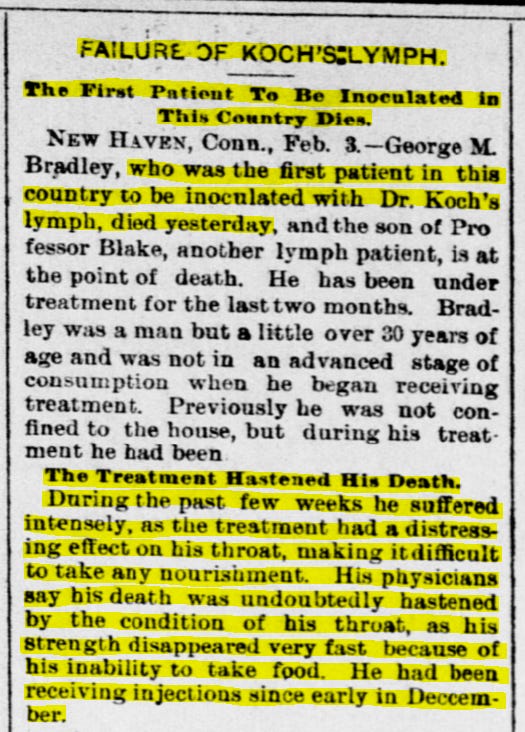

The excitement of Koch’s remedy was short-lived. Tuberculin was not only declared to be of no value, but decidedly dangerous, as outlined by the Glasgow Medical Journal.

“Its fame was short-lived. Robert Koch had made an announcement which could not be backed up by results. In the spring of 1891, but a few months after its introduction, at the annual meeting of the British Medical Association, tuberculin was declared to be not only of no value, but decidedly dangerous. It exhausted the strength of the patient; it led to the extension of the disease; it favoured the production of cavities; it not infrequently caused the death of the patient.”

The introduction of tuberculin as a “cure” for tuberculosis was a fiasco—Dr. E. A. Duncan reported in 1924 that many patients died as a consequence of the poisonous injections.

“On Koch’s recommendation tuberculin was hailed with enthusiasm as a cure for tuberculosis and its use begun. It was administered in what we would regard today as massive dosage and the results were disastrous. All over Germany the poor patients were “‘todespritzt’’—injected to death—as this doctor put it. This fiasco resulted in prompt abandonment of tuberculin.”

“In August 1890, Robert Koch dramatically announced that he had discovered a cure for tuberculosis, and the world rejoiced. The miracle substance was subsequently revealed to be tuberculin, inoculated as a ‘vaccine therapy’. However, within a matter of months his claims were disputed and debunked, and his reputation was grievously damaged.”

Koch’s scandal caused a severe setback in public optimism toward bacteriological innovation, as maintaned by a 2002 publication.

“The repercussions had both adverse and effective consequences. The widespread public disappointment caused a severe setback in public optimism toward bacteriological innovation.”

A publication in Medical History (2001) recounts that with the failure of tuberculin, the whole conception of tuberculosis centred on the pathogen started to slip. Bacterial reductionism was criticized for its non-scientific conception of disease.

“It seems that with the failure of that cure the whole conception of tuberculosis centred on the pathogen started to slip. This can be shown in minor details, such as when Koch’s critics from Pettenkofer’s school in Munich managed to produce his tuberculin reaction by the means of extracts of entirely different bacteria. In addition to this, we find, immediately after the tuberculin scandal, a whole set of fundamental critiques of Koch’s bacteriology. Some critics, such as Heinrich Lahmann, criticized it as illustrating the hypocrisies of scientific medicine. Others, more surprisingly, accused Koch’s bacteriology of mysticism. Bacterial reductionism, which had been regarded as the peak of scientific medicine in the early 1880s, was now censured for its ontological conception of disease, which appeared to be non-scientific … Although the tuberculin disaster probably did a lot to discredit the concept of infectious diseases as bacterial invasion, there is no indication that Koch himself realized this erosion of his work.”

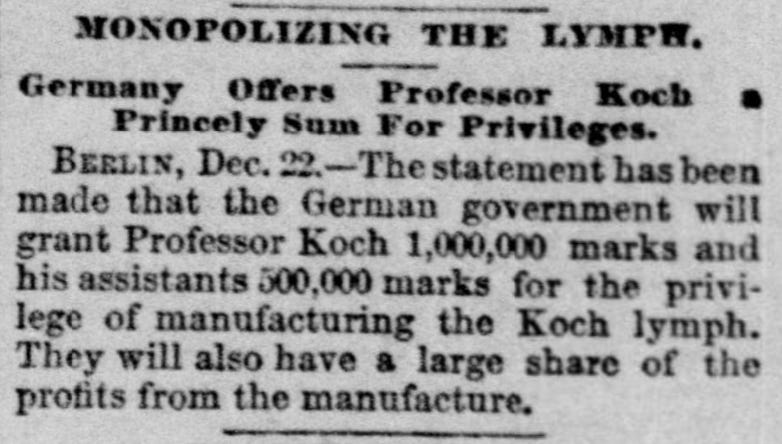

“Koch’s tuberculin for tuberculosis excited greater hope and greater disappointment than any other nostrum, the preparation of which was kept a secret, for the apparent purpose of enriching Professor Koch, thus making it a quack medicine.”

Some contemporaries and historians have postulated that Koch was a deceiver with ulterior motives.

“The issue of Koch’s ideas about tuberculin includes a question I have not yet posed: namely, whether he thought he had a remedy at all. The notion of a “tuberculin fraud” has been put forward by contemporaries and historians and some features of his conduct are indeed hard to comprehend, if one entirely excludes the notion of Koch being a deceiver. He supplied scarce and misleading information about his cure, for example, by linking it rhetorically to the well-established and successful disinfection. When criticized, he was unable to show the guinea pigs he had cured with tuberculin. Further, the manner in which Koch pursued his commercial plans ended up in mutually attempted blackmail by himself and Prussian government officials.”

Pasteur’s Rabies Deception

Louis Pasteur’s rabies investigation began in the late 1800s. However, his initial attempts to establish the etiology of rabies were unsuccessful, as described by the Pasteur Institute.

Dissolving the Myth of Tuberculosis Contagion

The disease now called tuberculosis was formerly known as consumption, phthisis, the white plague, and scrofula. Keep this in mind when reading through the historical texts in this article.

Robert Koch's Vicious Human Experiments in Africa

After his tuberculin disaster in the early 1890s, Robert Koch looked for new fields of research. To make up for his failures in Europe and restore his prestige as a renowned scientist, Koch took to the study of tropical disease in Africa.

Was Koch's "tuberculin" the same "tuberculin" used for the TB test? Apparently to this day they inject subcutaneous tuberculin and if there is a "larger than normal skin reaction" this means you "have tuberculosis." They apparently do this to livestock and euthanize any animal "testing positive".

Sounds insane to me since I don't know why people would think injecting foreign proteins into your skin would do anything other than randomly produce a reaction (e.g., allergic).

Fantastic exposé of the fraud Dr. Robert perpetrated to bring a dangerous product to market. Interestingly, the press and medical community seemed far more honest back then—publicly calling out tuberculin, and watching the entire scheme backfire on the doctor in what can only be described as a bit of a Koch-up.

It seems Big Harma took notes. They've since turned that early blunder into a riotous success, building an iatrogenic business model of spiraling, circular profits—offering expensive 'solutions' to the very harms their products cause, all while a paid-off media chorus chants "safe and effective" from the sidelines.