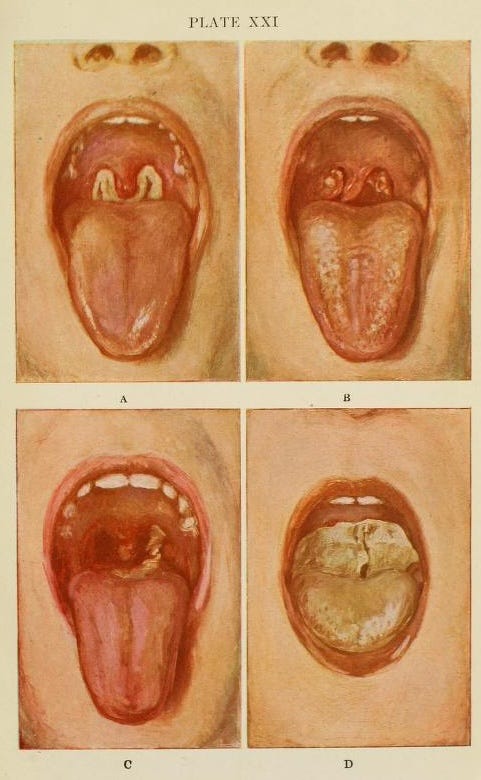

Diphtheria is said to be a contagious disease which is characterized by an inflamed throat. In severe cases, a grey coating develops in the throat, called a pseudomembrane.

The disease is purported to be caused by a toxin produced by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, also known as the Klebs–Löffler bacillus, because the German bacteriologists Edwin Klebs and Friedrich Löffler (also called Loeffler) is said to have discovered the bacterium that allegedly causes diphtheria, in the late 1800s.

Edwin Klebs (1883) did not perform any experiments, he simply discovered the presence of the bacterium in people with diphtheria, and assumed a causal association.

Under the section Etiology in the 1895 book entitled Diphtheria and Its Associates, it is declared that Klebs did not establish a causal relationship between the bacterium and diphtheria.

“To Klebs, therefore, the credit of having discovered this organism is undoubtedly due. But since he never definitely announced that he had been able to obtain pure cultures of it, it must be said that he failed in establishing its causal relationship to the disease.”

A mere association between a microorganism and a disease does not establish causation, as stated by Dr. Herbert Snow in 1913.

“Hence a natural temptation, whenever a micro-organism is found in connection with a malady, to assume that the latter is directly due to the former, and to overlook necessary links in the chain of scientific proof.”

Further, the Dr. Snow describes how there is ample evidence contradicting the causal association between microorganisms and disease.

“There has never been anything approaching scientific proof of the causal association of micro-organisms with disease; and in most instances wherein such an association has been pretended, there is abundant evidence emphatically contradicting that view.”

This fact became evident to Friedrich Loeffler, who could not detect the presence the Klebs-Loeffler bacterium in all cases of diphtheria.

Rather than admitting to be wrong, Loeffler made up excuses as to why his belief could still be true despite evidence to the contrary, known as the ad hoc rescue.

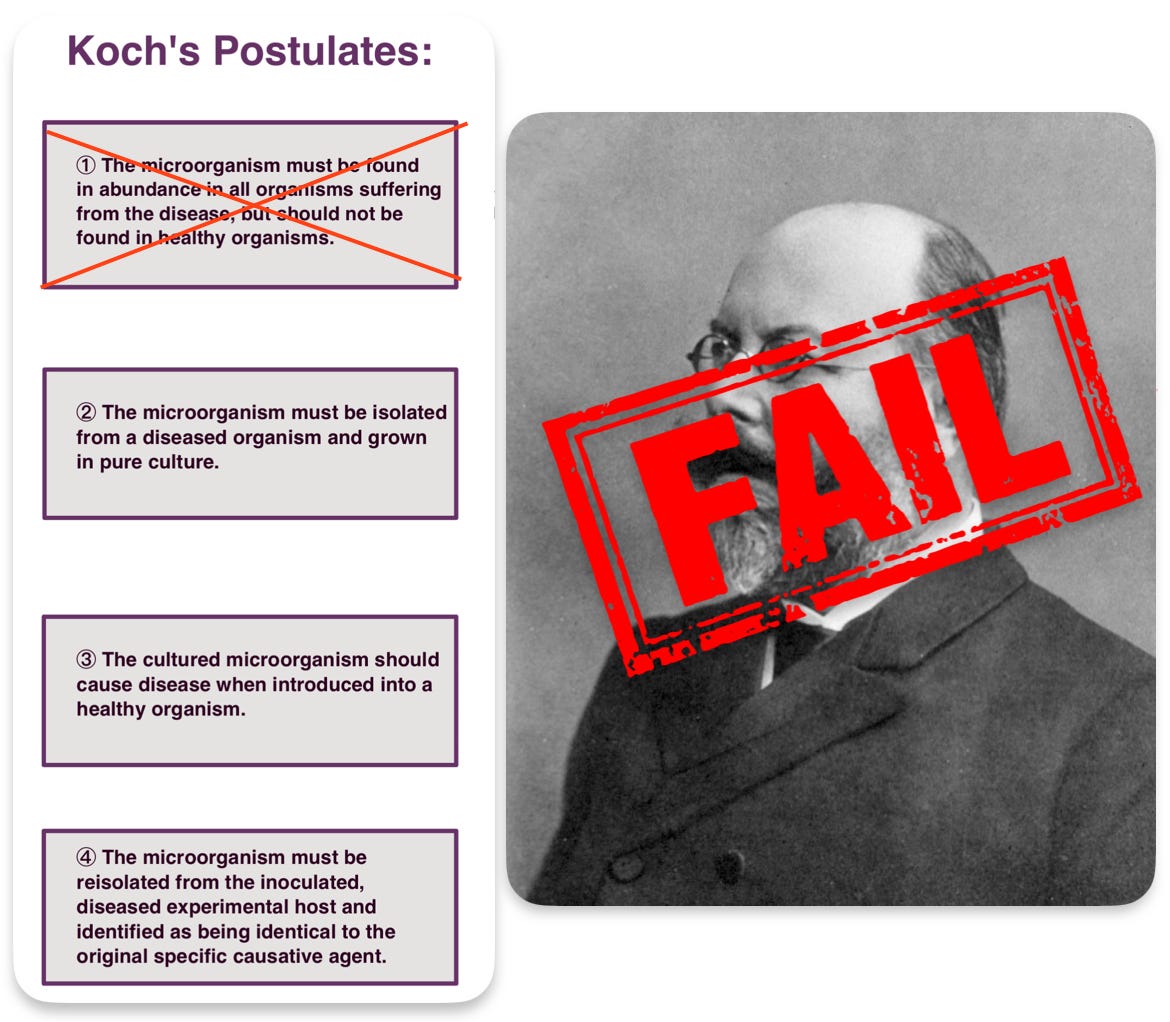

Robert Koch and Friedrich Loeffler formulated Koch’s postulates, which are four criteria designed to establish a causal relationship between a microbe and a disease. The first postulate states that the microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease.

In his 1895 publication entitled Ueber die Beziehungen des Löffler’schen Bacillus zur Diphtherie, Dr. David Hansemann critically examines the germ theory of diphtheria. On page 364, he quotes Friedrich Loeffler’s admission how he falsely corroborated Koch’s first postulate in diphtheria by labeling the cases where the bacterium was absent as something different.

“The pathogen of diphtheria is the diphtheria bacillus. However, since there are illnesses that appear clinically as diphtheria, but in which the bacillus is missing, all of these illnesses must henceforth be separated from diphtheria as something completely heterogeneous. Only where the bacillus is present is there genuine diphtheria.”

[Translated using an online translator.]

The term “pseudo-diphtheria” was thus born. Cases of diphtheria where the Klebs-Loeffler bacterium was missing was diagnosed as such, as described by a 1891 article.

“Pseudo-diphtheria. This term is employed through want of a better one. It is proper to state in this connection that clinical observations and experiments, carefully made, have demonstrated the fact that certain other microbes besides the Klebs-Lœffler bacillus, sometimes produce a pseudo membranous inflammation upon the faucial or other surface, which as regards its anatomical characters, appears to be identical with that in true diphtheria. The only differerence thus far discovered has been the absence of the Klebs-Lœffler bacillus.”

Loeffler could therefore claim that the bacterium was present in all cases of the diphtheria, because the presence of the microbe was a necessary prerequisite for the diagnosis of diphtheria.

Friedrich Loeffler (1884) is claimed to have established a causal relationship between the bacterium and diphtheria by inoculating animals with cultured bacteria.

However, the use of highly invasive methodologies does not reflect the hypothesized mode of transmission; his results can thus not be extrapolated to external conditions.

This non sequitur fallacy was outlined by Dr. John Fraser in 1939.

“If you ask the germ theorist to point out the relation between injecting germs into small animals and giving humans the same germs in food or drink, they have to admit that these are two distinct procedures with practically no relationship.”

The problem with invasive routes of exposure such as injections is that the administered substances bypass all natural protective mechanisms of the body. Oral exposure is a completly different toxicokinetics than exposure through injection. Toxicokinetics describes how the body handles a substance, in terms of the concept of ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination).

What occurs in the body after the injection of a substance can not be positively compared to what would occur in the body by a different route of exposure.

“Loeffler found they [bacteria] were not present in a number of undoubted cases of diphtheria; that in the false membrane he produced by introducing them through a wound in the trachea in rabbits and fowls … that they produced no effect in several animals otherwise susceptible to their action when applied to the uninjured mucous membrane of the fauces, respiratory passages, eyes and vagina.”

Bacteriologists attempts to induce diphtheria in animals by means of natural pathways were unsuccessful according to Dr. Hansemann, on page 374.

“It has never been possible to make animals sick with diphtheria naturally. All attempts, by adding it to food or by inhalation, have been futile and have had entirely negative results.”

Loeffler’s diphtheria experiments were not accompanied by any control experiments, which is a considerable weakness.

In his 1895 on diphtheria, Dr. John Macintyre describes how Dr. David Hansemann opposed the animal experiments purporting to demonstrate transmission. Hansemann, criticized the invasive methodologies used, and that the injury afflicted was ignored. He stated that chemicals and other microorganisms could likewise induce diphtheria by the same routes of exposure.

“He next criticised the animal experiments, and maintained that subcutaneous injections might set up serious infiltrations and hyperæmia of the kidneys; that on uninjured mucous membranes the bacillus often produced no effect. It might of course produce fibrous exudation on an injured mucous membrane, but the same results could be produced by chemicals and other micro-organisms ... The guinea-pig was susceptible to Loeffler’s bacillus, but never to spontaneous diphtheria.”

Animals experiments concerning diphtheria was likewise brought into question by Drs. Horatio Wood and Henry Formad in their 1882 publication entitled Memoir on the Nature of Diphtheria, originally published in the National Board of Health Bulletin.

Wood and Formad injected animals with material from people with diphtheria into rabbits. However, the rabbits developed tuberculosis, rarely diphtheria.

“These experiments seem to warrant the deduction that inoculation with materials taken from patients suffering from the endemic mild diphtheria of Philadelphia frequently produces a secondary or indirect tuberculosis in the rabbit, but very rarely, if ever, causes any disease in the rabbits comparable to diphtheria in man.”

Wood and Formad performed experiments to determine if organic irritants other than diphtheric material may induce diphtheria in animals.

“To see whether organic irritants other than diphtheritic exudations will produce a pseudo-membranous trachitis, the following experiments were performed:”

They inoculated rabbits with normal pus and various foreign bodies. The animals developed symptoms of diphtheria by the inoculation of normal pus, which succeeded in a larger proportion than with diphtheritic material from a previous experiment.

“In looking over the last table, it will be seen that in two of the ten experiments pseudo-membranous trachitis was caused by the introduction of organic matter into the trachea. In both of the cases in which false membrane was produced the injected material was pus; and it will be noticed that only four such experiments were made, so that the proportion of successful result is very large; larger, indeed, than with true diphtheritic exudation in our experiments.”

Inoculations with material from gangrene also induced diphtheria.

“We have also made several inoculations with material taken from a case of what might be termed hospital gangrene … These experiments seem to show that this so-called spreading or hospital gangrene is capable of producing in the rabbit symptoms and lesions similar to those caused by diphtheritic exudation.”

Drs. Edward Curtis and Thomas E. Satterthwaite also came to the same conclusions in their experiments.

“It would seem therefore that the disease produced in the rabbit by inoculations of diphtheritic matter, is not only not specifically diphtheritic in character, but not even peculiar to the diphtheritic infection; since a disease essentially similar, if it be not pathologically identical, is produceable, though in variable intensity, by inoculations of material at once non-diphtheritic and non-infectious to human mucous-membrane.”

Drs. Wood and Formad referenced another researcher who demonstrated that various chemicals irritants are capable of causing diphtheria. Wood and Formad acknowledged that diphtheria is a non-specific manifestation which can be induced by any irritant of sufficient intensity.

“Trendelenburg found that not only ammonia, but also various other chemical irritants are capable of causing the formation of false membrane in the trachea. Many years since it was proven that tincture of cantharides will do the same thing. It would seem, therefore, that in the trachea the formation of a pseudo-membrane is not the result of any peculiar or specific process, but simply of an intense inflammation which may be produced by any irritant of sufficient power.”

The following conclusions were drawn:

“It is difficult to produce in the rabbit a rapid septic disorder with the matter taken from ordinary cases of so-called diphtheria … Both septic animal matter and non-organic irritants placed in the trachea cause pseudo-membranous trachitis which cannot be distinguished from diphtheritic trachitis … The occurrence of a false membrane in the trachea is the result not of the specific character but of the intensity of the inflammation.”

Their conclusions align with the results of other researchers; who only succeeded in a small proportion of the attempts to produce diphtheria in animals, as outlined by the 1889 book entitled Diphtheria: Its Nature and Treatment.

“In the recorded experiments for the communication of diphtheria to the lower animals by inoculation it is to be observed that the operation is attended with great uncertainty, succeeding in only a small proportion of all cases; that it has usually failed when attempted in the mucous membrane of the mouth and fauces, but has much more often succeeded in the trachea.”

Although some researchers have induced paralysis in animals by the inoculation of Klebs-Loeffler bacteria and its derivatives, they are undermined by the fact that “a number of workers have also caused paralysis in experimental animals simply by injecting normal nervous tissues.”

No hypothetical pathogen is required in diphtheria, since the signs and symptoms have been shown to be caused by various non-microbial substances.

Such was reported a 1896 publication entitled Is Membranous Croup Always Due to the Microbe of Diphtheria?.

“It is established, both experimentally and clinically, that pseudo-membranous inflammations of the throat may be produced by a variety of causes, such as inhalations of hot vapour, the swallowing of corrosive poisons, etc.”

In his 1891 article entitled The Etiology of Diphtheria, Dr. J. Lewis Smith describes how diphtheria can be caused by various irritating agents and poisons.

“M. Talamon states that not only other microbes, a besides the Klebs-Lœffler bacillus, but also certain irritating medicinal and chemical agents, have the power to excite an inflammation with fibrinous exudation upon the faucial, or other surface, to which they are applied, which cannot be distinguished by its appearance and anatomical characters from that of true diphtheria except by the absence of the cause of the latter disease, to-wit, the Klebs-Lœffler bacillus. The inflammation produced by non-microbic irritating agents, as steam, boiling water, chlorine, cantharides, and ammonia.”

A similar statement can be found in the 1895 book Diphtheria and Its Associates.

“False membranes of essentially the same macroscopic and microscopic character as those of truly diphtherial origin have been reported as produced on the mucous lining of the buccal cavity and air-passages by every kind of traumatism, as, for example, irritant poisons, solid, fluid, or gaseous, scalding water, scorching heat, chemical or galvano-caustics, or even strong Eau-de-Cologne. Oertel performed the experiment of dropping a few minims of liquor ammoniæ into the trachea of seventeen animals, and succeeded, in every instance, in generating an artificial croup.”

This should not be a surprise even to bacteriologists, given that their designated pathogen is frequently absent in cases of diphtheria.

In a 1926 publication, it was reported that “bacterial examination is not infrequently negative in just those cases of diphtheria which are most serious.”

Careful investigations from various hospitals over the world showed that the Klebs-Loeffler bacilli was only detected in 50-80% of diphtheria cases.

“The results from these hospitals are all the more valuable because the cases came from all parts of the various cities in which the respective hospitals were located, and hence special local conditions were not likely to greatly influence the general results obtained. Thus Baginsky, in Berlin, found the diphtheria bacilli in 120 out of 154 cases; Martin, in Paris, in 126 out of 200; Janson, in Switzerland, in 63 out of 100; Morse, in Boston, in 239 out of 400; and Park, in New York, in 127 out of 244. Thus from 20 to 50 per cent. of the cases sent to diphtheria hospitals did not have diphtheria.”

In an analysis of 5611 cases of suspected diphtheria, the bacterium could only be found in 60% of the cases.

The Results of the Bacteriological Examination of 1,000 Cases of Suspected Diphtheria showed that “in 40.9 per cent., or about two-fifths, of the cases, the diphtheria bacillus was not found.”

In the 1912 Report of Royal Commission on Vivisection, it was found that the bacterium was absent in 20% of cases.

The Klebs-Loeffler bacterium was not found in 28% of diphtheria cases, as reported in The Principles and Practice of Medicine, published in 1915.

In a 1898 article from The Lancet, it was stated that the bacterium was not present in 14% of diphtheria cases.

“The true Loeffler’s bacillus was often found in healthy throats, and also sometimes in the generative passages of healthy women. On the other hand, in what might be termed to be undoubted cases of diphtheria (clinically) it was very often not found after continued and careful examination.”

The purported causal relationship between the microbe and diphtheria is further weakened by the fact that the bacterium is frequently found in healthy people.

“Humans are the usual reservoirs, and carriers are usually asymptomatic.”

The WHO states that most “infections” are asymptomatic.

“Most infections with C. diphtheriae are asymptomatic”

The ubiquitous nature of the diphtheria bacilli was affirmed by professor Ulrich Friedemann in 1928, who stated that in one year about one-third of the population are “infected” with the Klebs-Loeffler bacterium without contracting the disease.

“We come to the conclusion that in one year about one-third of the population is infected with diphtheria bacilli without contracting the disease.”

The higher proportion of bacterial presence in symptomatic individuals is not surprising, considering the saprophytic role of bacteria in nature; breaking down devitalized organic material. This was understood as early as 1896 by Dr. Elmer Lee.

“It is undoubtedly true, that suitable nourishment for the growth of germs is found in the throats of children whose general system is impaired with diphtheritic sepsis. The so-called specific germ is found upon the tonsil both in health as well as in disease. Is it, therefore, a reliable means of determining the diagnosis of diphtheria?

Is the explanation of the false membrane which forms upon the throat, thus interfering with respiration, to be found by bacteriologic inquiry? When the system is impaired, and a determination of the weakened vital forces results in an inflammation of the fauces, there is thrown out upon the mucous membrane a thick, tenacious, glairy fluid, which dries and thickens into a membrane. The inflammatory state of the mucous membrane keeps adding fresh serous discharges, thus augmenting the deposit and ultimately filling the free space of the throat. In this serum the colonies of a variety of germs find normal food for nourishment and growth.”

The belief in the germ theory of diphtheria was in odds with clinical experience, which meant that new diagnoses such as “pseudo-diphtheria” had to be used.

“The differential diagnosis between diphtheria and so-called pseudo-diphtheria is of great importance. The latter condition may be defined as an inflammation of the mucous membrane of the throat, accompanied by the formation of pseudo-membrane which resembles that of true diphtheria, in which the Klebs-Löffler bacilli are absent.”

In the 1915 book The Principles and Practice of Medicine, it is stated that there was a great discrepancy between the clinical and bacteriological diagnosis.

“The diagnosis of the Klebs-Loeffler bacillus is regarded by bacteriologists as the sole criterion of true diphtheria, and as this organism is associated with all grades of throat affections, from a simple catarrh to a sloughing, gangrenous process, it is evident that in many instances, there will be a striking discrepancy between the clinical and bacteriological diagnosis.”

The use of unsubstantiated bacteriological tests that were in odds with clinical signs was condemned by Dr. Herbert Snow in 1913.

“A very important misuse of the Germ Theory lies in the substitution, sometimes enforced officially, of artificial and unreliable diagnostic methods for the previous reliance upon clinical signs. This is in the highest degree prejudicial to medical education, tending to develop an academic race of practitioners devoid of practical acquaintance with their calling as healers of men, relying upon book-knowledge and artificial tests for disease, bigoted and narrow in an extreme degree. The fallacy of a microscopic test founded on the presence or absence of a particular germ, for any special malady whatever, is conspicuous in every single instance already stated. No microbe can invariably be detected in cases indisputably of the malady with which its name has been associated. Every such micro-organism has been over and over again detected when there could be no suspicion of the malady it was supposed to bring.”

Friedreich Loeffler failed to fulfill the postulates he himself helped to formulate.

That Kleb-Loeffler bacteria are innocuous when experimentally introduced into the body through normal pathways was demonstrated by Dr. John Fraser, who published his results in a 1916 issue of The Canada Lancet. Fraser and six volunteers swallowed millions of active Klebs-Loeffler bacilli in milk, bread, fish and alone, without any subsequent ill-effects.

“The first test was whether the Klebs-Loffler bacilli would cause diphtheria, and about 50,000 were swallowed without any result; later 100,000, 500,000 and a million and more were swallowed, and in no case did they cause any ill-effect.”

[…]

“The investigations covered about two years and forty-five (45) different tests were made giving an average of fifteen tests each. I personally tested each germ (culture) before allowing the others to do so; and six persons (3 male, 3 female) knowingly took part in the tests and in no case did any symptom of the disease follow.

The germs were swallowed in each case, and were given in milk, water, bread, cheese, meat, head-cheese, fish, and apples also tested on the tongue.

Most of the cultures were grown by myself some from stock tubes furnished by Parke, Davis & Co., and one tube furnished by the Toronto Board of Health through one of their bacteriologists.”

The same negative results were obtained by Dr. Matthew Rodermund, who “sprayed the poisons of diphtheria … into the throat, nose [of his patients], or had them breathe into the lungs, repeating the experiments in most cases every one or two weeks for months with the result that no disease could be developed.”

Exposure to the sick was likewise not accompanied by danger.

Dr. Walter Scott reported in a 1937 publication published in The Lancet, the results of a careful investigation into the problem of “The Contact in Industry.” With regard to diphtheria he found that, over a period of ten years, out of 7697 contacts with the disease, only 0.36% subsequently developed the disease.

“Diphtheria contacts amounted to 7697, and of these only 1 contact in every 274 cases (0.36 per cent.) subsequently developed the disease.”

It has to be remembered that cases coinciding with contact is inevitable.

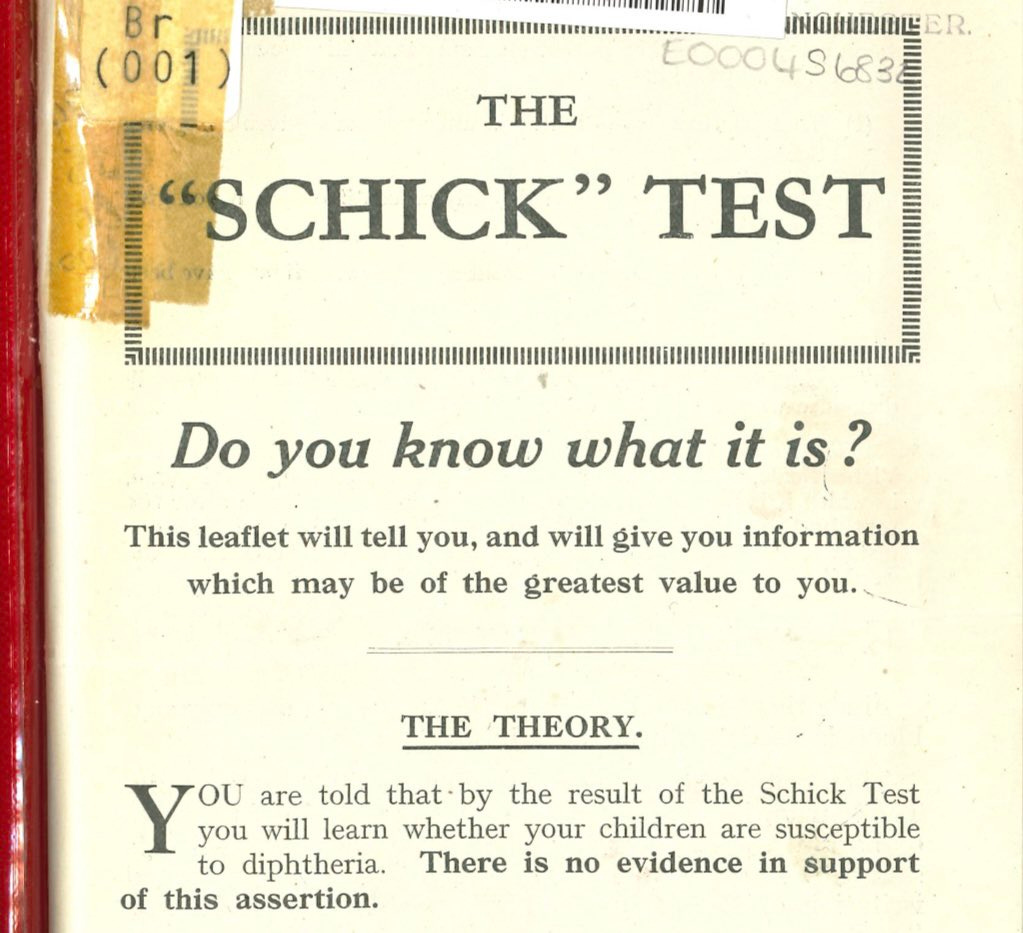

The Schick test was developed for determining susceptibility to diphtheria. The Schick test consists in injecting a small quantity of the toxin of the Klebs-Loeffler bacilli into the skin, and is therefore based on the belief that the germ is the cause of the disease.

A positive reaction, it is claimed, indicates susceptibility; a negative reaction, immunity from diphtheria.

“By the use of a simple test (Schick test), it is possible to find out those children who are liable to take the disease and those who are not.”

A diphtheria vaccine was developed as well. It consisted of diphtheria “antitoxin” combined with a neutralized form of the Klebs-Loeffler toxin.

The theory of immunity is based on the assumption that exposure to the purported bacterial toxin will provoke a condition of “immunity” in the body which will protect it from further attack. It is believed that in both the naturally acquired and the artificially induced disease, protection is brought about by the development of “antitoxin” in the blood of the individual.

However, repeated attacks of diphtheria were not unusual, which is a fact that is difficult to reconcile with the theory of immunity.

In a book published in 1902 entitled Quain’s Dictionary of Medicine, it is stated that one attack of diphtheria does not confer immunity.

“One attack of diphtheria confers no prolonged immunity upon its subject. Even during convalescence the patient has been known to develop the disease afresh, and this may be repeated more than once.”

Dr. Claude Buchanan Ker wrote in his 1922 publication A Manual of Fevers, that it was quite common to suffer from diphtheria more than once.

“Second attacks are quite common, many persons suffering twice, or even more frequently, from diphtheria.”

It is difficult to imagine that the immunity which natural diphtheria cannot give to the child may be produced by vaccination.

A closer scrutiny reveals that the theory of immunity did not correspond to clinical experience.

In his 1939 publication entitled The “Schick” Inoculation for Immunisation Against Diptheria, Dr. Maurice Beddow Bayly’s thorough examination disclosed that “many authorities have reported undoubted cases of diphtheria in patients giving a Schick-negative reaction.”

In an article entitled Should the Schick Test be Abandoned? in the American Journal of Public Health, 1925, Dr. Wilfred H. Kellogg, Director of the Bureau of Communicable Diseases, California State Board of Health, asserted that the Schick test should be abandoned on account of its unreliability.

“In this paper evidence is presented to support the contention that the Schick test for diphtheria susceptibility should be abandoned absolutely, not only in private but also in public health practice.

An extensive and accumulating experience in the Schick testing of large groups of persons, both children and adults, and the retesting of them after toxin-antitoxin immunization, has brought to light a number of sources of error that constitute a danger both from a public health standpoint and as regards the welfare of the individuals concerned.”

Using statistics from numerous countries, Dr. Bayly uncovered ample “positive evidence of the failure of inoculation to immunise.”

In Ireland for example, a vaccination campaign “was greatly hampered by the continual occurrence of reported cases of diphtheria among treated or partially-treated children.”

In Germany, opinions about the value of immunization against diphtheria were conflicted. Several writers had reported cases of diphtheria in which the Schick test were negative.

“Though wholesale immunization against diphtheria has been undertaken in Germany during the past few years, opinions are yet divided about its value. It would seem that there is at present no criterion by which the degree of protection against diphtheria afforded by active immunization can be gauged. Schick himself was of the opinion in 1922 that a negative Schick test put diphtheria out of court; but several writers have reported cases of diphtheria in which the Schick test was negative.”

Several statistical fallacies were brought about that contributed to favourable results of vaccination, according to Dr. Maurice Bayly.

“There remain to be considered the fallacies which afford an explanation of apparently favourable statistics.”

These mainly relate to a hesitation in diagnosing diphtheria in patients with a presumed immunity, as outlined in Dr. Bayly’s publication.

“But in addition to this fundamental change of front there has to be mentioned another alteration in diagnosis. This consists in the refusal to classify cases as diphtheria among the immunised, on the ground that they only present mild symptoms. According to the Medical Officer of Health for Ipswich (see East Anglian Times, February 22nd, 1934), it has become the practice not to regard as diphtheria persons who, after immunisation, develop sore throats even though the presence of the Klebs-Loeffler bacilli (hitherto considered to be diagnostic of the disease) can be demonstrated in them.

Such a manoeuvre is not only bound to falsify all subsequent vital statistics, but can be shown to be unjustifiable on grounds of medical pathology, for the assumption that mild cases are not likely to be diphtheria is not borne out by historical records.”

Conclusion

The claim of the Klebs-Loeffler bacterium to be considered the causal agent in the production of diphtheria is unsupported by scientific evidence; with abundant evidence emphatically contradicting that view.

The “Schick” Inoculation for Immunisation Against Diptheria by Dr. Maurice Beddow Bayly is a comprehensive document about the danger and fallacies of diphtheria immunization. Kindly provided by John Wantling.

In his article entitled Emil Von Behring’s Diphtheria/Tetanus Papers (1890): Precursor to Antibodies, Mike Stone details the history and discovery of the so-called diphtheria antitoxin.

The Fallacy of Antitoxin Treatment as a Cure for Diphtheria by Dr. Elmer Lee is self-explanatory.

If you know German, Dr. David Hansemann’s publication Ueber die Beziehungen des Löffler’schen Bacillus zur Diphtherie is a refutation of the germ theory of diphtheria.

Outstanding article, thank you .

Great piece.

The likes of Klebs and Löffler would be seen as the bumbling charlatans they were if they did not have the power of vested and ideological institutions supporting them. This is the case with every single one of these "microbe hunters" from past to present.

As an addendum to your excellent article in the early 1890s, Emil Von Behring and Shibasaburo Kitasato reported that serum taken from experimental animals who had been immunized against the "diphtheria toxin" could be used to prevent and treat "diphtheria" in humans.

Von Behring, considered by some to be the “father of immunology,” went on to develop the first "diphtheria" antitoxin and started the first human trial of serum therapy against "diphtheria" in 1892. He was awarded the first Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1901 even though his initial serum formulation was unsuccessful due to poor serum quality.

Recent investigation reveals this legendary figure to have employed fundamental methodological tricks that apparently rigged the outcome of his experiments. A detailed analysis found that he was “pretreating” the lab animals by giving them therapies “designed to alleviate toxicity.”

An exposition of von Behring’s work observed that he was “pretreating his cultures and animals with iodine trichloride and zinc chloride and using these substances to ‘disinfect’ the toxins in the cultures, gradually ramping up the doses, and thus providing the illusion of “immunity.”

Von Behring openly admitted that “immunity was not permanent and that unfavorable conditions left the animals to the same disease as if they had not been immunized.”

In 1896, the first indications that serum therapy might cause adverse events appeared when a healthy infant died from what was believed to be an anaphylactic reaction to the serum. In the child’s obituary, the father—a well-known pathologist—declared that his son’s death was “due to the injection of Behring’s serum for immunization.”

The poor-serum problem was purportedly resolved when Paul Ehrlich, considered the “father of chemotherapy,” developed standardized measuring techniques and used larger animals (horses) to derive "diphtheria" antitoxin. Later it was discovered that the horse-derived antitoxin was also associated with anaphylaxis and serum sickness.

In 1907, Dr. Charles Page asked the question, “Diphtheria: Is the Prevailing Antitoxin Treatment Only Another Medical Delusion?,” in the title to his article published in Medical Brief, A Monthly Journal of Scientific Medicine and Surgery. Page believed that improvements in sanitation would be a more effective remedy for diphtheria.

Page’s sentiment was echoed by Dr. James Cumming in an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1922.

Cumming pointed to the fact that mortality rates from "diphtheria" had decreased over the previous 30 years, before "diphtheria" toxoids were widely used.

He attributed this decrease to improvements in hygiene and sanitation:

“The eradication of diphtheria will not come through the serum treatment of patients, by the immunization of the well, or through the accurate clinical and laboratory diagnosis of the case and the carrier followed by quarantine; rather it will be attained through the mass sanitary protection of the populace subconsciously practiced by the people at all times.”(JAMA, 1922, p. 682.)

Nevertheless, despite the correlations between "diphtheria" and poverty, poor social conditions, poor nutrition, and poor sanitation—and despite the accompanying statistical decline of "diphtheria" in developed countries as those conditions improved—the march towards wholesale vaccination continued apace. Starting in the late 1940s, the "diphtheria" nostrum was incorporated with the tetanus toxoid, pertussis vaxx and this combination vaccine was routinely used by doctors to immunize patients against these three diseases.

It's all racketeering.